Mesoamerican Prehistory Timeline

List of Peoples

(These links connect to the beginning of the period in which the group is mentioned. Only one reference is provided per group, normally the time of the group’s first or major appearance in the archaeological record.)

Aztecs, Chichimecs, Chontàl Maya, Esperanza Phase People, Huastecs, Itzà Maya, Izapàn Maya, Kaqchikèl [Cakchiquel] Maya, K’ichè’ [Quiché]Maya, Mam, Maya, Mixe-Zoqueans, Mixtecs, Mogollón, Olmecs, Otomí, Pipìl, Pokomàm Maya, Putùn Maya, Purépecha, Spanish, Tapachultecs, Tarascans, Teotihuacanos, Tèpenacs, Toltecs, Totonacs, Tzutuhìl Maya, Zapotecs.

List of Periods

- Geological Background

- Early Hunters 11,000± – 7,000± BC

- Archaic (Incipient Farming) Period 7000± – 2000± BC

- Early Formative (Pre-Classic) Period 1500/1800-900 BC

- Middle Formative (Pre-Classic) Period 900-300 BC

- Late Formative (Pre-Classic) Period 300 BC – AD 300

- Early Classic Period (Mexico: AD 150-650/Maya: AD 250-600)

- Late Classic Period AD 600-900

- Early Post-Classic Period AD 900-1200

- Late Post-Classic Period (part 1) AD 1200-1400

- Late Post-Classic Period (part 2) AD 1400-Spanish Conquest

Appendix: Table of Aztec Monarchs

More detailed chronology of the Aztecs

Geological Background

- 50,000-7000± Wisconsin Glacial Period

- 38,000-34,000, 30,000-15,000 The presence of land corridors from Beringia allows the possibility of human passage, but convincing evidence is still wanting. Click here for more information on the Bering Strait Land Bridge

- >11,500 Cary Advance

- 11,000-10,000 Mankato Advance (humid)

- 10,000-8000 Two Creeks Interval (dry)

- 9000-7000 Valders Advance (humid)

- 8000 Sea levels rise, ending Bering Straits Land Bridge (Beringia)

- 7000-2000 Hypsithermal (European “Climatic Optimum”)

- 5500-4800 Cochrane Advance in Canada (humid) (=Younger Dryas Event)

- 2000 BC – AD 1800± Little Ice Age

- 1500-150± BC (humid)

- 150± BC – AD 900 (dry)

- 900 – 1800± (humid)

- Return to very beginning, list of periods, list of peoples.

1. Early Hunters Period 13,000±? to 7,000± BC

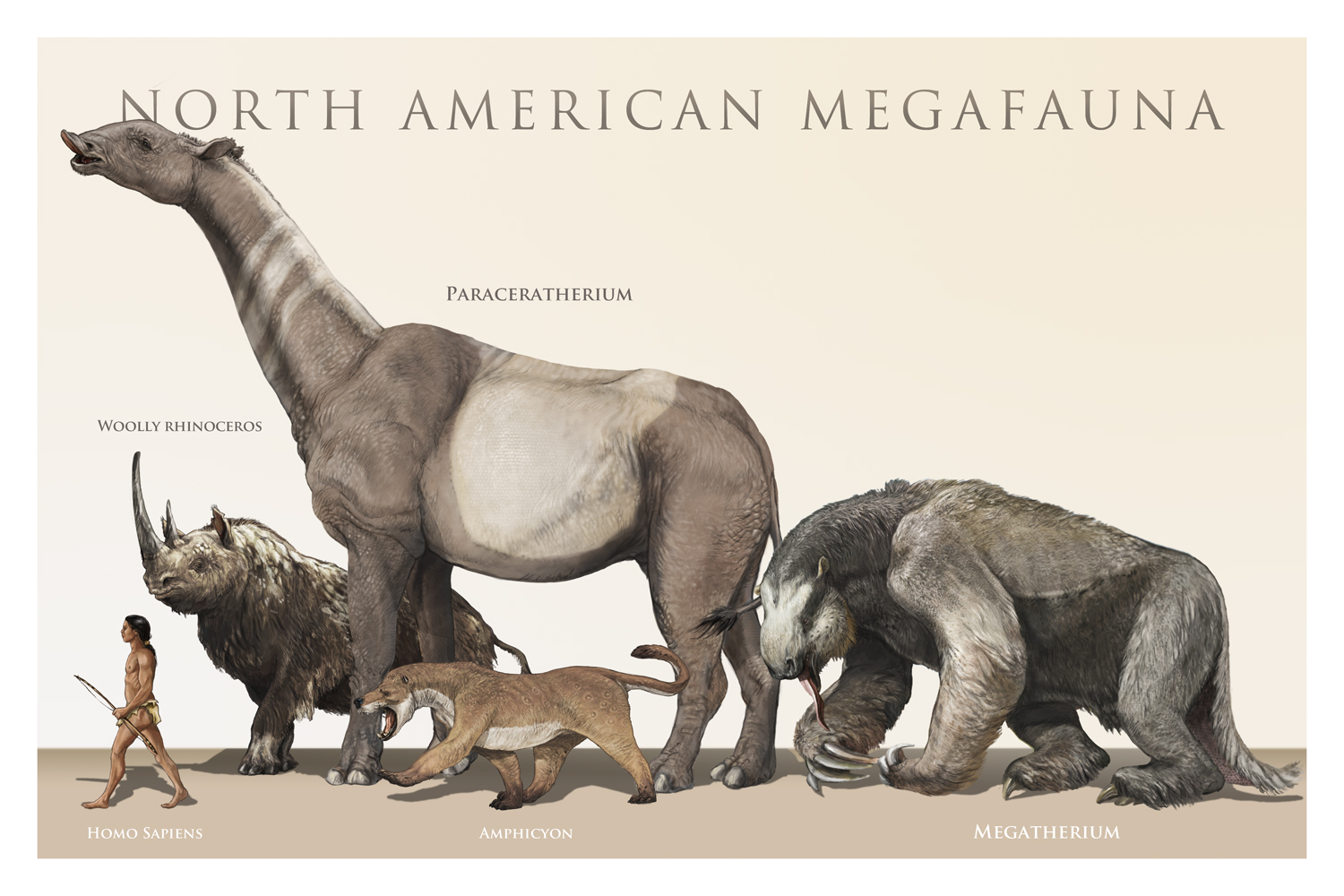

- Nomadic foragers; fishing; some seed collection.

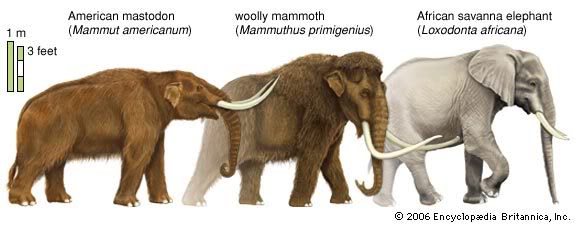

- 11,000-10,500 (formerly 9500-9000) Clovis points in North America used in mammoth hunting.

- 8000 Folsom bison points in North America.

Mexico: Northern Mexico (Tamaulipas)

- 11,000-10,000 Diablo Phase.

- unspecialized foraging tools.

Mexico: Central Highlands

- >7000 Tehuacán Ajuereado Phase.

- bands of 12-15 people; some big-game hunting.

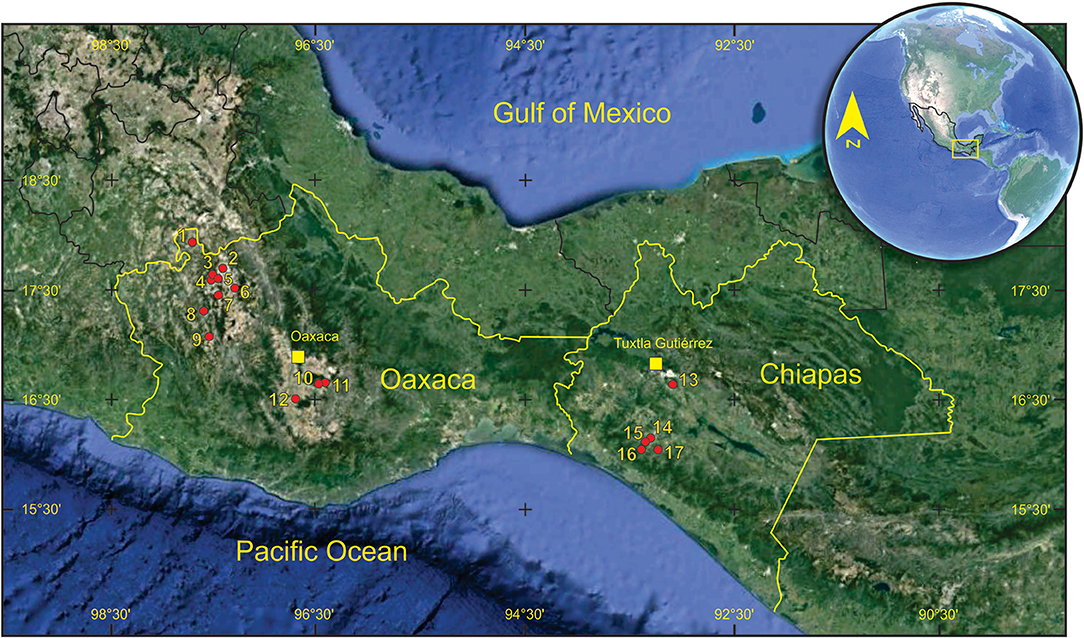

Mexico: Oaxaca Valley

- Long Sequence parallels Tehuacán.

- 7400-6700 Zea pollen; bottle gourds; pumpkin.

Maya Areas:

- 11,000± Red ochre mined from caves in Yucatán

- Wild horses among prey

- 9000-7500 Lowe-Ha Phase in northern Belize; very small nomadic bands

2. Archaic (Incipient Farming) Period 7000± – 2000± BC

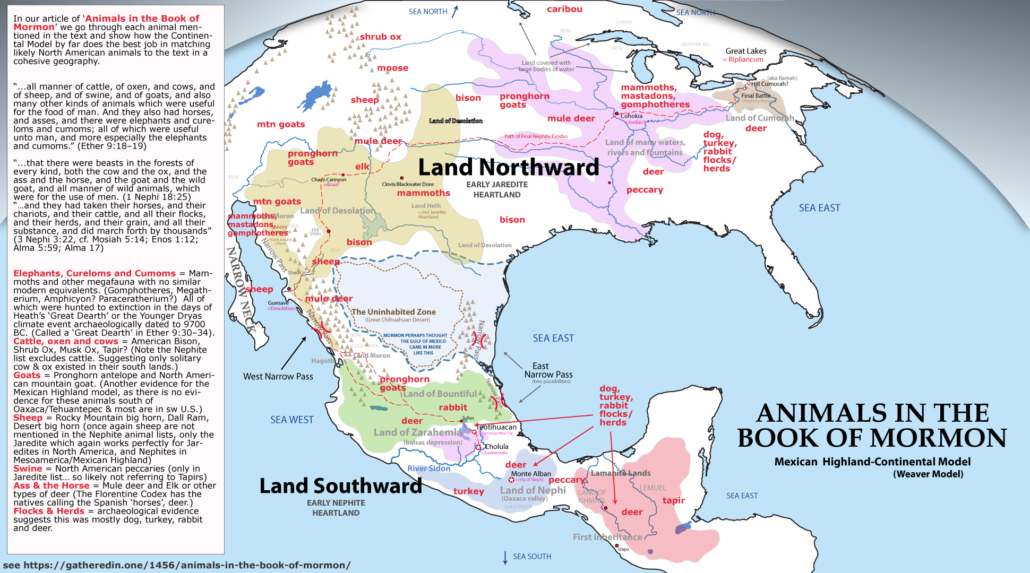

- Gradual development of horticultural skills, some signs of fixed settlement, possibly some shamanism; extinction of many animals; Desert Cultures of US West and northern Mexico (Tamaulipas &c.).

Mexico Central Highlands

- Tehuacán (Puebla) Phases:

- 7000-5000 El Riego Phase.

- Cotton; ritually damaged buried bodies; seasonal nomadism.

- 5000-3400 Coxcàtlan Phase.

- Bottle gourds, beans, new squashes, first maize.

- 3400-2300 Abejas Phase.

- Small hamlets of 5-10 pithouses; hybrid maize, tepary beans, pumpkin?; 30% of diet made up of cultigens; ground stone containers.

- 2300-1500 Purrón Phase.

- crude pottery appears in two shapes, probably by diffusion from Caribbean or South America.

- Tlapacòya: Female figurines of 2300±100 BC oldest in Mesoamerica.

Mexico: Balsas Depression

- 2000± Maize probably composes majority of human diet according to finds in Balsas River Valley.

Mexico Oaxaca Valley

- Long Sequence parallels Tehuacán

- 7000-5000 Wild and probably domesticated corn found in Puebla-Oaxaca.

Mexico Gulf Coast

- Probable cultivation of manioc without archaeological traces.

Maya Areas

- 7000-3500 Santa María Complex (Chiapas) similar to Tehuacán & Tamaulipas Archaic, and to “Desert Culture” further north.

- 2000± first division of hypothetically unitary Proto-Maya language into Huastecan, Yucatecan, and southern variants; Huastec migration to Veracruz & Tamaulipas; southern group divides into two language groups: (North-)Western (Chol of Tabasco) and (South-)Eastern (Mam & K’ich’è [Quiché] of highland Guatemala).

- Broadly savannah-like environment (destined to be forested AD 300±)

- Some maize grown!

- Belize Archaic

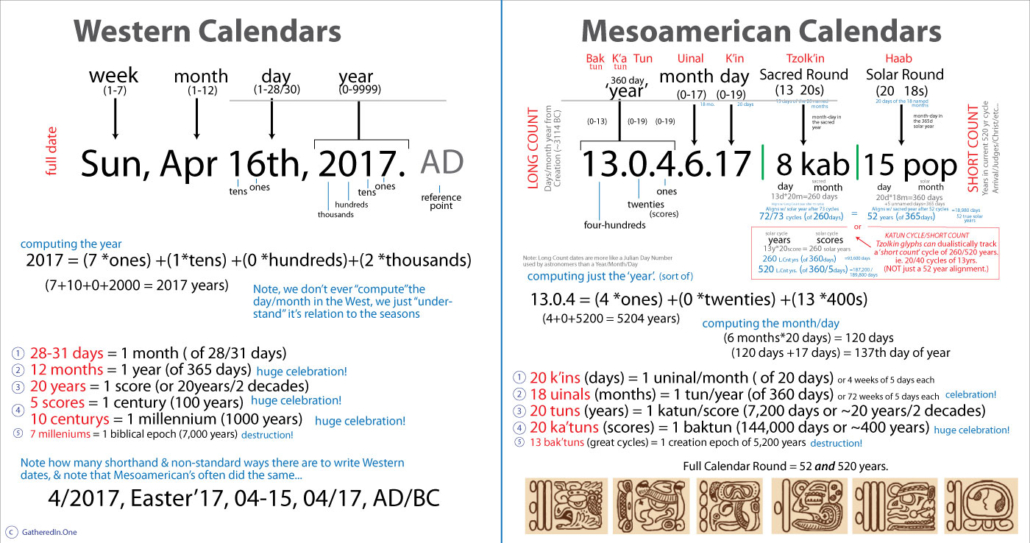

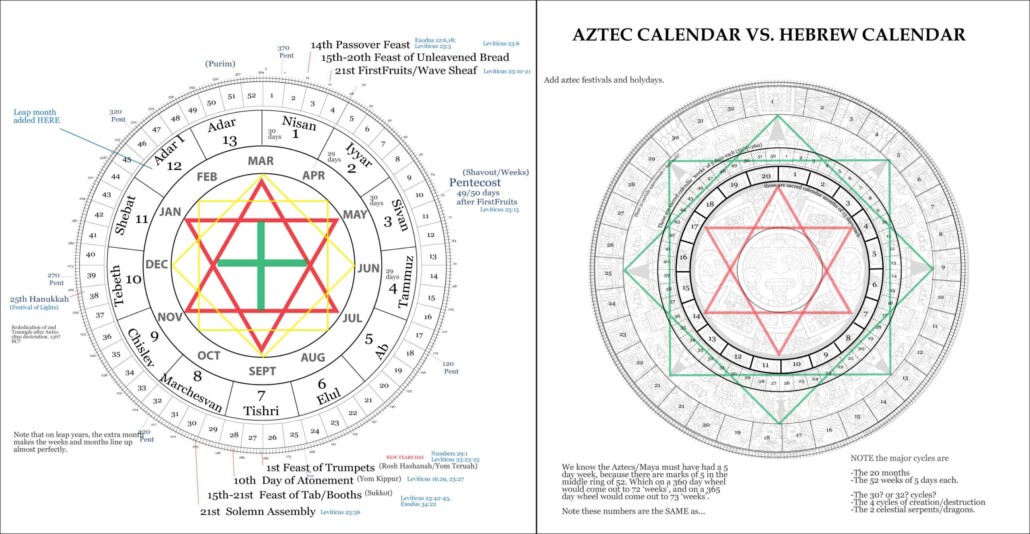

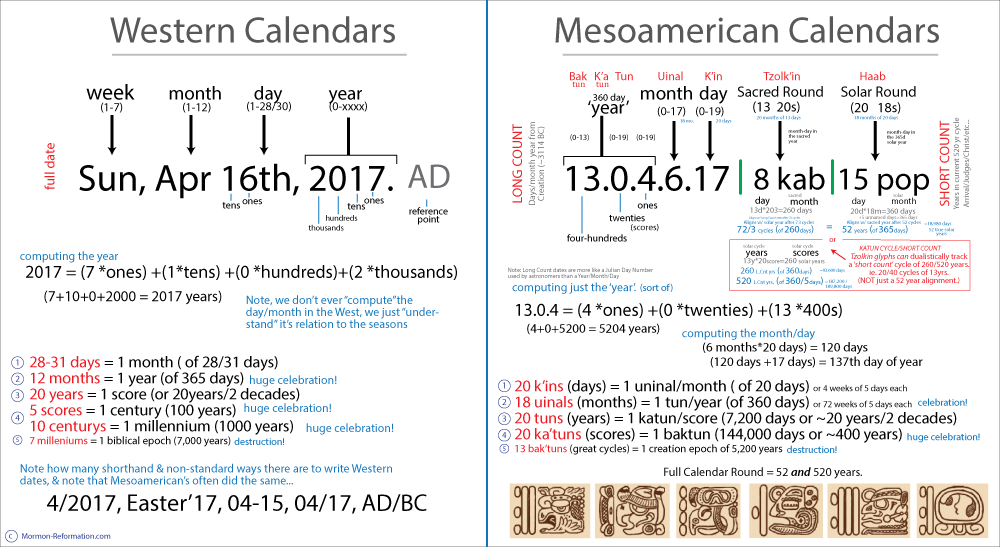

- August 13, 3114 BC (Gregorian): Starting point (0.0.0.0.0 4-Ahàw 8-kumk’ù) of Classic Maya Long-Count Calendar

Other Parts of the World

- 6150± Çatal Hüyük a major Neolithic center in Turkey

- 2600± Great Pyramid built

- 2350± Sargon of Akkad destroys Babylon (which rises again)

- 1700± Founding of Chinese Shāng dynasty

3. Early Formative (Pre-Classic) Period (Mexico: 1500-900 BC; Maya Area: 1800-900 BC)

- “Neolithic” farming villages; pottery, looms, ground stone figurines; rule by groups of elders, shamans, or chiefs; rain & fertility cults; regional differentiation.

Mexico Central Highlands

- figurine cults.

- 1100 Zacatènco.

- 1200 Tlatìlco: large, rich village; storage pits, animal and human sculpture; 340+ burials.

- 1350 El Arbolillo.

Mexico: Southernmost Mexico (Chiapas)

Beginning of Chiapa de Corzo sequences running from 1500 to the present in Grijalva Depression.

Mexico Oaxaca Valley

- 1150-850 San José Phase

- San José Mogote: village of 80-120 households with maize, chili, squashes, avocados.

Mexico Gulf Coast

- 1750-1500 Earliest evidence of cacao (chocolate) use by Pre-Olmec peoples of the Gulf coast. (Click here for More About Cacao. )

- 1400-900 San Lorenzo (Veracruz) earliest of the major Olmec sites, a major Olmec center by 1200; first religious ceremonial center in the New World; earliest ball court; stone drains; spectacular sculptures, including colossal heads; probable cannibalism; bufotenine (frog-derived) hallucinogens.

- >1000 San Lorenzo Destroyed.

West Mexico

- Juxtlahuàca Cave, near Colotlìpa (Guerrero) with polychrome “Olmec” murals, contemporary with San Lorenzo Olmec?

Maya Areas

- Beginning of Chiapa de Corzo sequences running from 1500 to the present in Grijalva Depression.

- 1000± Arévalo phase at Kaminaljuyù (Guatemala). Burial mound shows class distinctions, viz priest buried with riches, a commoner with nothing, possibly not correctly dated to this phase.

- 1900-1500 villages of the Mokaya people along the Pacific coast of Chiapas include ceramics with traces of cacao (Click here for More About Cacao. )

- 1800 villages along coast at Soconusco (Xoconòchco), Guatemala

- 1800 Barra Phase huts, decorated pottery, possibly used for stone-boiling, in forms similar to Purrón ware of Tehuacán; maize cultivation; clay figurines; no evidence of social classes. Gives way to fully agricultural Ocós

- 1700-1500 Locona Phase; stamper-rocking, cooking vessels, social hierarchy.

- 1500-1400 Ocós Culture of La Victoria (near Soconusco); fully agricultural combined with marine animals; first cord-marked pottery in New World; female “goddess” figurines similar to those of Ecuador from 3700± BC

- 1200 Cuadros Culture; Nal-Tal maize production.

- 1000-700 Swasey/Bladen Phase at Cuello (Belize) exhibits popcorn, yams; plaster platforms; ceramics with no known stylistic predecessors and some ressemblance to later forms.

- Tz’ibilchaltùn [Dzibilchaltún] (Yucatán) occupied from 1500 or 1000 BC till conquest by Spanish, never an important center, but little else is known about the area in the Formative.

Other Parts of the World

- 1350± Babylon assimilated into Assyrian Empire

- 1200± Fall of Troy, Mycenae, and other Archaic Greek states, beginning the “Greek Dark Ages”

- 1000± Jerusalem conquered by King David

4. Middle Formative (Pre-Classic) Period 900-300 BC

Olmec civilization; widespread trade; diffusion of Olmec traits in many directions; class divisions. Spread of Mayan speakers into Lowlands seems to have occurred in this period.

Mexico Central Highlands

- Lakeside sites (lake fish, deer, birds; skilled uses of obsidian):

- El Arbolillo (three-legged bowls).

- Zacatenco (many clay figurines, usually nude women.

- Tlapacoya & Cuicuilco the first purely religious structures in the Valley of Mexico.

- 800 Tlatilco increased class differences.

- 700-500 Cantera Phase in Morelos.

- 1400 -500 BC Chalcatzingo: An Olmec “peripheral site”; artificial terraces; Olmec-style sculpture. Monumental archetecture at 700 BC.

West Mexico

- Oxtotitlán Rockshelter (Guerrero) with polychrome “Olmec” murals, contemporary with La Venta Olmec?

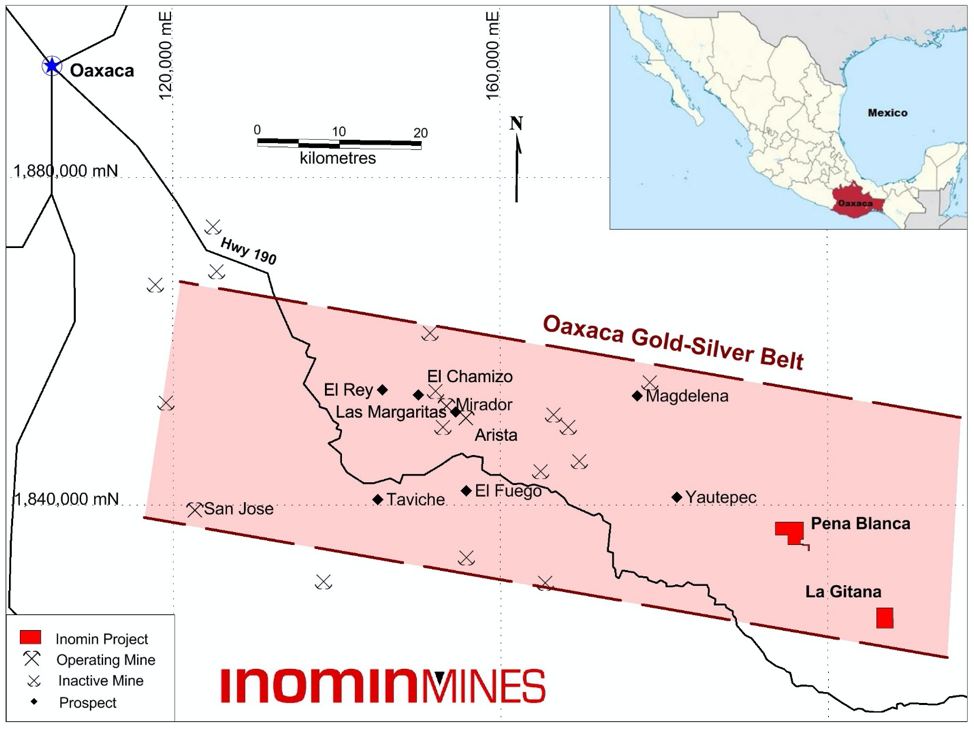

Mexico Oaxaca Valley

- San José Mogote remains most important site; hieroglyph of proto-danzante possible forerunner of later Zapotec script.

- 600 – 200± Monte Albán I Phase. Writing & calendar, probably borrowed from Olmecs.

- 500-450 Monte Albán founded on commanding hilltop site, with 10,000 to 20,000 inhabitants by end of Early Formative times; danzante reliefs with clear hieroglyphic texts, still undeciphered. Calendar Round in use.

Mexico Gulf Coast

- Height of the Olmec civilization; astronomy, sculpture, writing, calendar?

- 1000-400 or 400 La Venta (Tabasco)

- Greatest Olmec site, but hinterland poorly understood; Tres Zapotes (Veracruz) First Occupation, contemporaneous with La Venta.

Maya Areas

- Maya languages now spread throughout roughly their historical range.

- Conchas Phase.

- 500-300 Las Charcas phase widespread, but centered at Kaminaljuyù with excellent decorated pottery.

- 700-400 Mamóm village culture phase at El Mirador, Waxaktùn [Uaxactún] & Tik’àl with red-orange pottery (rarely decorated), first seen in Swasey Phase at Cuello (Belize) dating about 1000-700 BC.

- Nak’bè shows platforms layered on older ones.

- Altùn Ha (Belize) only known Mamòm public architecture

- Xe Phase at Altar de Sacrificios & Seibal

- 900-400 BC Uìr Phase at Copán (Honduras) has Olmec-like features, probably because Olmec jade seekers found Copán area jade deposits

- Maní Cenot Phase, followed by Yucatán Middle Pre-Classic.

Tz’ibilchaltùn [Dzibilchaltún] with Mamòm-like Nabanchè phase

Other Parts of the World

- 753 Town of Rome founded

- 586 Nebuchadnezzar destroys Jerusalem

- 551 Confucius born

- 478 Themistocles of Athens founds the Delian League

5. Late Formative (Pre-Classic) Period (Mexico: 300 BC – AD 150; Maya Area: 300 BC – AD 250)

- “Urban Revolution”: building of the great urban centers, new social class divisions.

- (Note: If there were trans-Pacific contacts, they would have occurred sometime before the end of this period, since the “shared cultural traits” were then in place. However neither material goods nor diseases seem to have moved across the sea by this time, so “shared cultural traits” must be provisionally attributed either to chance or to parallel developments from traditions that antedate the last of the Beringia migrations.)

Mexico Central Highlands

- 300-1 BC Teotihuàcan I Phase.

- AD 1-300 Teotihuàcan II (=Tzacualli?) Phase.

- Pyramid of the Sun constructed.

- AD 150 Volcano destroys Cuicuilco, leaving Teotihuàcan unrivaled in the Central Highlands.

Mexico West Mexico

Balsas (=Mezcala) River sites (Guerrero) develop Mezcala art style; shaft tomb art in Nayarit, Jalisco, and Colima states.

Mexico Oaxaca Valley

- 250± BC – 1 BC Monte Albán II Phase.

- Many peoples involved in stages I & II, probably including ancestors of modern Zapotecs; Maya influence till beginning of Classic; building J constructed.

- AD 1 – 500 Monte Albán IIIa Phase.

- Zapotecs definitely now the people involved.

Mexico Gulf Coast

- Probable invention of Long Count calendar. (Some say it was invented as early as the 8th century BC.)

- Tres Zapotes (Veracruz), Second Occupation .

- Stele C (dated to 3 Sept 32 BC).

- La Mojarra stela 1 with two long-count dates, AD 143 and 156

- “Isthmian”-style Tuxtla statuette (possibly in Mixe-Zoquean language) with long count date of AD 162

Maya Areas

- Oldest Long Count date of 7.16.3.2.13 (7 December 36 BC) found at Chiapa de Corzo (Chiapas).

- Izapa (Chiapas) founded in Early Formative by Tapachultec (Mixe-Zoquean) speakers and persisting to Early Classic, with height in Late Formative.

- Olmec-derived but idiosyncratic art style; the principal transmitting tradition between Olmec & Maya societies, with wide influence; possibly forerunner of Classic Maya configuration.

- Izapa-like Miraflores phase of Kaminaljuyù, its Golden Age, including effigy vessels and widespread Usulutàn yellow-on-brown ware; mushroom stones; irrigation; water storage.

- Santa Clara Phase, Aurora Phase.

- AD 36 Herrera Stele, earliest dated sculpture in Maya region at El Baúl

- Abàj Tak’alìk’ (Chiapas), like El Baúl a “Maya” site within a generally Cotzumalhuapa area

- Izapan culture at Izàpa (Chiapas)has wide influence, possibly forerunner of Classic Maya configuration.

- Chikanèl [Chicanel] Phase at Waxaktùn [Uaxactún] and elsewhere; cement-plastic-stucco surfaces widely used

- Temples built at El Mirador, Tik’àl & Waxaktùn [Uaxactún] (Guatemala) and Cerros & Lamanai (aka Indian Church) (Belize); tombs with vaults.

- Enormous Danta and Tigre pyramids at El Miradór.

- Matzanel Phase.

- Yucatán Late Pre-Classic, very similar to Chicanel; site of Yaxunà.

Other Parts of the World

- 63 BC Birth of Augustus, to become first Roman emperor

- 255 BC Qin dynasty ends Chinese feudalism & establishes Chinese imperial system

- 206 BC – AD 219 Chinese Han dynasty

6. Early Classic Period (Mexico: AD 150 – 650; Maya: AD 250 – 600; Traditionally AD 300-600 for both areas)

For the Maya, the Classic is now more formally defined as the interval during which Long Count dated monuments were erected in the lowlands.

Consolidated states with substantial social class differentiation; long-count calendar, writing, sculpture, mathematics, ceramics, and large-scale urban planning widespread in many areas; strong Izapan influence continues in Maya areas.

Mexico: Central Highlands

- Teotihuàcan III (=Miccoatli?) Phase: the height of Teotihuàcan, with much influence elsewhere. People of unknown name sometimes called Teotihuacanos.

- 200 Pyramid of the Moon & Ciudadela (“TFS”) constructed, the latter dedicated with about 200 human sacrifices.

- (By the end of the Early Classic there were about 40 times as many people in the Valley of Mexico as during the Middle Formative, and Teotihuàcan probably had a population of about between 100,000 and 200,000 people, its maximum.)

Mexico: Oaxaca Valley

- Classic period for Monte Albán with major temples built.

- 500-900 Monte Albán IIIb population estimated at 24,000; 170 underground tombs with frescoes.

Maya Areas:

- Mexican (probably Pipil) culture at Santa Lucía Cotzomalhuapa arises in late Early Classic with strong interest in death & ball games.

- 400 Kaminaljuyù, occupied by Teotihuacanos, becomes miniature version of Teotihuàcan. Long Count calendar vanishes.

- Esperanza Phase of Kaminaljuyù, a kind of Maya-Teotihuàcan hybrid. (Teotihuàcan influence has been traced as far as Nicaragua and Costa Rica.)

- Teotihuàcan-influenced Tzak’òl phase of Waxaktùn [Uaxactún] & Tik’àl; dawn of Classic Maya culture till 600. Teotihuàcan domination is now judged more likely due to conquest than to local Maya emulation, although new evidence could change this.

- Tik’àl’s Leiden Plate (AD 320), stele 29 (AD 292), and possibly Humberg stele (AD100?) earliest known Long Count objects in Maya area.

- 250± Yax Moch Xoc founds Tik’àl dynasty

- 378 Siyàh K’ak’ arrives from El Perú to the west at Tik’àl or Waxaktùn, possibly leading an invasion force from Teotihuàcan; Waxaktùn [Uaxactún] falls to Tik’àl

- 426? Yax K’uk’ Mo’ founds dynasty at Copán (Honduras) which continues to 585±

- Destruction of many sites toward end of Early Classic probably due to revolt & local warfare, both possibly linked to major drought peaking about 585 and/or to fall of Teotihuàcan about 600.

- Rich graves of Río Azul sites (looted in 1960s & 1970s)

- Bekàn [Becán] fortified town in Chenes region suggests warfare before Teotihuàcan conflict

- Akankèh [Acanceh] shows Mexican-style buildings; Regional Styles.

Other Parts of the World

- 391 Christianity becomes state religion of the Roman Empire

- 476 Western Roman Empire collapses

7. Late Classic Period (AD 600-900)

(In the Maya area the term “Terminal Classic” refers to the period from 800 to 925 or so. Various states collapse late in this epoch: Monte Albán, Mexican-influenced Kaminaljuyù, Copán are either destroyed or abandoned. Cultural florescence of Puuk [Puuc] hills of northern Yucatán late in this period.

Mexico: Central Highlands

- Teotihuàcan IV.

- 600-700 Teotihuàcan destroyed by fire, probably by Chichimecs. (Most Teotihuàcan influence on other sites ended by about AD 600. The fire is dated differently by different writers.)

- Production of related Coyotlatèlco ware by squatters on the site continued for an additional 200 years.

- 700± Xochicàlco (Morelos) founded, apparently with Maya contacts.

- 860 Xochicàlco “Fortress” built.

- 800-900 pre-Toltec Corràl Phase at Tula.

- 700-1292 Olmeca-Xicallanca (= Putùn Maya = Chontòl) dynasty at Cholula (Puebla), site of largest pyramid in the New World.

- Cacàxtla (Puebla) site of Putùn Maya enclave in Mexico in 8th & 9th centuries.

Mexico: Oaxaca Valley

- Monte Albán declining, to be abandoned about 900

Mexico: Gulf Coast

- Classic Veracruz culture (sometimes claimed to resemble Bronze Age China, despite misfit of dates). (The modern Totonac people live in this region today, and Classic Veracruz people are sometimes called Totonac.)

- El Tajín (Veracruz), the most important Classic Veracruz site, reaches its height about 900. Obsessive interest in ball games.

- Remojadas (Veracruz) produces pottery figures of same name, resembling Classic Maya sculptures.

Maya Areas:

- Occasional but increasingly severe droughts after about 650 begin to reduce crops and increase warfare.

- Cotzomalhuapa Phase continues at El Baúl, associated with Nàhuatl-speaking Pipìl on Pacific Piedmont and showing traits of Maxican Gulf Coast.

- Earliest evidence of tobacco (possibly for medicinal use) found through analysis of resideues in pottery in Mirador basis of soutrhern Campeche.

- 682 Copán meeting of astronomers fixes lunar-solar calendrical correlation

- 683 Chahn-Bahlum succeeds Sun Lord Pacal and the latter is magnificently entombed at Palenque.

- Tik’àl Major temples built; largest Maya site with 10 to 40,000 people.

- 695 Ruler 18 Rabbit (Waxaklahùn Ubàh K’awìl) enthroned as 13th monarch of Copán, begins huge building project.

- 735 Seibal falls to Dos Pilas

- 738 King Canac Sky of Quiriguá rebels; captures & beheads 18 Rabbit; Smoke Monkey accedes in Copán, builds Popol Nah of Copán.

- Tepeu culture

- Yaxchilán, Piedras Negras, etc major centers

- 751-790 Deterioration of alliance system

- 760-830 Protective walls built at Dos Pilas and Aguateca

- 792 Bonampak murals left unfinished

- 790-830 death rate exceeds birth rate across Petèn region

- 800± Probably about 8-10 million people in all Maya lowlands when unknown catastrophe strikes.

- 800-1050 Major drought, peaking about 862, may have interacted with inter-state warfare and with environmental degredation caused by high population levels to cause general collapse.

- 820 end of Copán dynasty founded by Yax K’uk’ Mo’

- 830 Construction stops except in peripheral sites.

- 849 “Wat’ul” mentioned in Seibal stele as coming from “Puh,” possibly Tula, since both terms mean “place of reeds.”

- 850± Chontàl and Putùn, both “Mexicanized Maya” of Tabasco and southern Campeche, begin to move into “fallen” sites like Seibal

- 900 Copán abandoned.

Maya Area: Yucatán Lowlands

- This region generally flourishes after the Petèn collapse.

- Mid-Peninsula sites of Río Bec, Chenes, Kobà [Cobá]

- Río Bec & nearby sites (Xpuhil, Hormiguero) exhibit “movie-set” false-fronts

- Development of Tulúm on the east coast, Jaina island necropolis off west coast.

- Puuk [Puuc] & Chenes Phases.

- Puuk [Puuc] Florescence: Labná, Sayìl, Uxmàl, K’abàh, Etz’nà [Edznà].

Other Parts of the World

- 618-906 Tang dynasty an era of Chinese internationalism

- 622 Hegira of Mohammed

- 732 Defeat at Tours & Poitiers stops Moorish advance north of Spain

- 800 Charlemagne crowned “Romanorum Gubernans Imperium”

8. Early Post-Classic Period (AD 900-1200)

Widespread militarism. This is the “Epoch of the Toltecs,” with influence as far as Yucatán. Factionalism & Chichimecs bring about Toltec fall about 1168 or so.

Mexico: Central Highlands

- Rise of Toltec Empire, centered at Tula (=Tollan) (Hidalgo). They dominate Mexico between about 1100 and 1200 and become a model on which later imperial states nostalgically look back.

- Between 800 & 1100 Toltecs enter “Civilized Mexico” under Mixcòatl and settle at Colhuàcan, later to arrive at Tula (Tòllan) under Topìltzin-Quetzalcóatl.

- 950-1150 or 1200 Tòllan Phase at Tula.

- Tula covered 14 sq km and held 30-40,000 people.

- 987± Exile of Topiltzin Quetzalcóatl(= Ce Àcatl Topìltzin) from Tula to “Tlapàllan,” possibly Yucatán. Conquest of Chichén Itzá.

- 1100s Factionalism & Chichimec pressures.

- 1156 or 1168 Tula destroyed by fire; Huèmac commits suicide at Chapultèpec; Toltec diaspora.

Mexico: Northern Mexico

- 900 Alta Vista (Zacatecas) control of Turquoise road replaced by control from Quemada (Zacatecas).

- Casas Grandes (Chihuahua) contemporaneous with Tòllan Phase Tula, culturally linked with Mogollón (locally pronounced “muggy-own”) culture(s) of the US Southwest.

Mexico: Gulf Coast

- El Tajín continues till burnt by Chichimecs about 1200.

Mexico: Oaxaca Valley

- Monte Albán IV: Monte Albán site used for royal burials by the Mixtecs.

- Monte Albán IV site of Lambityeco shows Maya influence.

- Mitla, a Zapotec town, becomes the Mixtec capital; expansion of Mixtecs during Monte Albán V (=Toltec & Aztec periods).

Maya Area:

- 900± Teotihuacanos leave Kaminaljuyù.

- Ayampuc Phase.

- Possible flow of refugees from Petèn in 900s.

Maya Area: Petèn Lowlands

- 900 Copán abandoned.

- 905 last dated Puuk [Puuc] style monument

- 910 Last recorded Long Count date (at Itzimtè).

- General depopulation of the Petèn

- Expansion of Putùn (=Chontòl = “Olmeca-Xicallanca”) Maya expand from around Xicallanco (Tabasco); they move to Campeche, where they are ejected about 1200, migrating to the Lake now called Petén Itzá, then to the site of Chich’èn.

Maya Area: Yucatán Lowlands

- Possible flow of refugees from Petèn in 900s.

- 987 Toltecs under “K’ulk’ulkàn,” possibly Topìltzin Qutzalcóatl, and seize the Maya town of Uukìl-abnàl (= Chich’èn Itzà)

- (Caution: A people called the Itzà established a later dynasty at the same site in the 1200s. The modern site name, Chichén Itzá, comes from that later occupation. It is convenient to refer to the pre-Itzà site simply as Chich’èn. The most famous buildings that the visitor sees on this site today date from the Toltec occupation period.)

- Toltec-Maya fusion seen in cult of the feathered serpent K’uk’ulcàn (Quetzalcóatl), possibly based on arrival of the refugee Toltec leader, in increase in human sacrifice, and in architectural features at new buildings at Chich’èn & Puuk [Puuc] sites.

- “Plumbate ware” found in Toltec-dominated Yucatán sites.

- Severe drought between 1000 and 1100 may have motivated out-migration and abandonment of settlements.

- Plumbate & Tojil Phases.

Other Parts of the World

- 1096-1099 First Crusade

- 1066 Norman conquest of England

- 960-1279 Song dynasty in China

9. Late Post-Classic Period (part 1) AD 1200-1400

Rise of the Aztec Empire; disintegration of Maya civilization.

(Note: By the time the Aztecs amounted to much, the Maya had disintegrated politically in all but a handful of mountain successor states. The Aztecs were not contemporary with major Maya states, and neither people knew about, cared about, or conquered the other. Grmpf!)

Mexico: Central Highlands

- 1230 Nathuatl-speaking Tepanec take over older town of Azcapotzalco.

- 1244 Nahuatl-speaking Chichimeca under Xolote settle at Tenayuca.

- 1250± non-Nahuatl-speaking Otomí found Xaltocan.

- 1260 Nahuatl-speaking Acolhua found Coatlinchan.

- 1325 Southern Aztecs (= Mexìca = Tenòcha) under Tènoc found Tenochtìtlan while northern Aztecs found Tlatelòlco just north of it.

- (A table of Aztec monarchs will be found in the appendix. For a detailed chronology of the Aztecs/Mexica, click here.)

- 1358 Northern Aztecs found Tlatelòlco just north of Tenochtitlan.

- 1359 Kingdom of Huexotzingo takes over sacred site of Cholula (Puebla).

Mexico: West Mexico

- 1325 Pátzcuaro founded on Lake of same name by Tarascan (Purépecha) hero Taríakuri. Ihuàtzio and later Tzintzúntzan eventually become capitals of Tarascan “Empire” in Michoacán.

Mexico: Oaxaca Valley

Mixtec States

Mexico: Gulf Coast

- 1200 El Tajín burnt by Chichimecs.

Maya Area: Yucatán Lowlands

- 1200-1224 Decline of Chich’èn Itzà and its abandonment by “Toltec” occupants.

- 1224-44 Itzà group of Putùn (“Mexicanized Maya”) leave Chakanputún (Campeche) and settle in ruins of Chich’èn, thenceforth known as Chich’èn Itzà (“Well Mouth of the Itzà”), using sacred cenote intensely.

- 1263 founding of Mayapán by Itzà leader K’ak’upakàl, possibly a Putùn from Tabasco. Mayapán’s dominance of surrounding territory is known as the League of Mayapán. (The site of Mayapán was actually first occupied in 941± by an earlier population.)

- 1283 Kokom lineage siezes Mayapán and subdues Northern Yucatán, forcing tribute from subordinates through a hostage system, but creating a city incapable of sustaining its population any other way.

- Further development of Tulúm island off east coast

Other Parts of the World

- 1206-1526 Sultanate of Delhi: height of Muslim rule of India

- 1223 Franciscan order founded

- 1245 Mongols rule all Russia

- 1276 Kublai Khan completes conquest of China

- 1300-1600 Renaissance in Europe

10. Late Post-Classic Period (part 2) AD 1400-Spanish Conquest

Mexico: Central Highlands

- 1427 Itzcoatl & Tlacaelel free the Aztecs.

- 1502 Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin & the major Aztec Expansion.

- 1519 Tenochtìtlan/Tlatelolco probably has 200,000 to 300,000 people.

- 1521 Spanish Conquest.

Mexico: Oaxaca Valley

- Mixtecs & Zapotecs largely successfully resist conquest by Aztecs, despite an Aztec assalts beginning in 1434.

- 1488 Aztecs raze Huaxyacac (Oaxaca City) and establish a garrison there.

- 1522-1523 Spanish take Oaxaca Valley; Aztec garrison town becomes Antequara, the Spanish regional capital for Oaxaca

Mexico: Gulf Coast

- 1518 Juan de Grijalva lands near Veracruz.

- 1519 Cempoala, the Totonac capital, conquered by Aztecs (They ally with Cortés soon afterward.)

- 1519 Cortés lands in Mexico.

Maya Areas:

- The K’ich’è [Quiché] at Utatlàn (Qúmaraqaj), controlled by an elite group probably descended from Putùn immigrants, and dominated by the Kawek family, dominate

- the Kaqchikèl [Cakchiquel] at Iximchè,

- the Pokomàm at Mixco Viejo, and

- the Mam at Zaculeu, and the Tzutuhìl.

- 1524 Pedro de Alvarado (died 1541) arrives in Guatemala highlands.

- Tecpán founded as Spanish HQ. Cakchiquel at Iximché ally with Spanish against Tzutuhil & K’ich’è [Quiché]. Tekùn Umàn, last K’ich’è ruler, killed by Alvarado near Quetzaltenango. Utatlàn, the K’ich’è capital, destroyed.

- 1525 Spanish conquest of Mam and Pokomàm.

- 1530 Kaqchikèl [Cakchiquel] chafe under Spanish domination and rebel. Spanish conquest of them at Iximchè.

- 1712 Tzeltàl rebellion in Chiapas.

- 1868 Tzeltàl rebellion in Chiapas.

- 1994 Tzeltàl rebellion in Chiapas.

- (This area is inaccessible [& gold-free] enough that Maya states continued for long after the fall of other areas.)

- 1450± Tayasal (Tah Itzà) founded at Lake Petén Itzá by Itzà refugees from Chich’èn.

- 1625 Spanish Conquest of Petèn Lowlands.

- 1697 Spanish Conquest of Tayasal, the final Itzà capital.

- 1524 Cortés is received by Tayasal King.

- 1695 Andrés de Avendaño visits Chak’àm on Lake Petén Itzá.

- 1450± Mayapán destroyed after feud between Xiw family of Uxmàl and Kokòm of Mayapàn; Itzà driven from Chich’èn.

- Small states squabble under local chieftains; fighting & disease; all large cities abandoned in general collapse

- 1517 Hernández de Córdoba discovers Yucatán, but is killed at Champotòn [Chakanputún].

- 1528 Francisco de Montejo lands in Yucatán and is repulsed.

- 1541 Spanish conquest of Yucatán.

- 1542 Founding of Mérida (Yucatán)

- 1847 Yucatán Rebellion against Mexican influence.

- 1860 Yucatán Rebellion against Mexican influence.

- 1910 Yucatán Rebellion against Mexican influence.

Other Parts of the World

- 1300-1600 Renaissance in Europe

- 1429 Jean d’Arc burned by the English

- 1492 Moors driven from Spain

- 1636 Harvard University Founded

- 1649 Manzhou conquest of China; Qing dynasty founded

Appendix: Toltec Monarchs

write here.

https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsAmericas/CentralToltecs.htm

Appendix: Aztec Monarchs

Spellings. Spellings in this table have been modernized to conform to modern standardized orthography of Classical Nahuatl, except that a dieresis (Umlaut) has been used instead of a macron to represent long vowels. Spellings in most books about the Aztecs will vary slightly.

Dates. Different sources disagree about the exact reign dates of some of Aztec monarchs, largely due to ambiguities in the original sources and in the Aztec calendar. Here are dates given by three painstaking authors as an example of the extent of the discrepancies.

| Monarch | Davies-1 | Orozco-2 | García-3 |

| 1. Äcamäpichtli | 1372-1391 | 1376-1396 | 1376-1395 |

| 2. Huïtzilihhuitl | 1391-1415 | 1396-1417 | 1396-1417 |

| 3. Chïmalpopöca | 1415-1426 | 1417-1427 | 1417-1424 |

| 4. Ïtzcöätl | 1427-1440 | 1427-1440 | 1425-1437 |

| 5. Motëuczomah Ilhuicamina | 1440-1468 | 1440-1469 | 1438-1471 |

| 6. Äxäyacatl | 1468-1481 | 1469-1481 | 1471-1479 |

| 7. Tizoc | 1481-1486 | 1481-1486 | 1480-1483 |

| 8. Ahuitzotl | 1486-1502 | 1486-1492 | 1483-1501 |

| 9. Motëuczomah Xöcoyötzin | 1502-1520 | 1502-0520 | 1502-1520 |

| 10. Cuitlahuäc | 1520 | 1520 | 1520 |

| 11. Cuauhtemoc | 1520-1525 | 1521-1525 | 1520-1525 |

| Nigel DAVIES 1973 The Aztecs. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. P. 305. Fernando OROZCO LINARES 1992 Fechas históricas de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial. Enrique GARCÍA EXCAMILLA 1995 Historia de México narrada en Nahuatl y Español de acuerdo al calendario azteca. Mexico City: Plaza y Valdés. |