This timeline goes along with our Book of Mormon timeline. Most notable is the idea that the Book of Mormon account of happenings after the Time of Christ which are dated in the text from 0 – 380 CE, correlate with the events among the Toltec, Chichimec/Aztlan culture of West Mexico, Southwest cultures and Cohokia which radiocarbon date from about 800 – 1180 CE. Two theories are provided to explain the dating discrepancy.

1599 CE – Don Juan de Oñate and 129 soldiers attacked and captured Acoma Pueblo, mutilating many survivors by cutting off hands and feet as punishment. —Roberts/Old Ones, p. 91)

1598 CE – Oñate’s conquistadors marched to New Mexico through Chihuahua (Lekson p. 214)

Arrival of Spanish colonists (Lekson p. 246)

1541

Coronado’s soldiers camped in the Texas Panhandle (Lekson, p. 26)

1540

Coronado arrived at Zuni and “took” the pueblo (Stuart)

By this date, Cahokia was gone (Lekson, p. 26)

Coronado’s armies entered the Southwest’s deserts looking for gold (Lekson p. 247)

to 1541

Francisco Vasqueze de Coronado, inspired be de Vaca’s stories, mounted an expedition into the Southwest (Lekson, p. 25)

to 1542

Coronado’s expedition (Stuart)

1539

Spanish arrived in pueblo country (Roberts p. 218)

1537

The Papal Bull, Sublimis Deus, issued by Pope Paul III declaring Native Americans to have souls (Lekson, p. 24)

1536

Cabeza de Vaca, the shipwrecked Spaniard, wandred through a corner of New Mexico (Lekson, p. 25)

1535

Coronado arrived in Mexico City (Stuart)

Pizarro conquered the Incas (Stuart)

1530

Nuno de Guzman, one of Cortes’s more difficult lieutenants, assembled a large army at Culiacan to search for the seven cities (Lekson, p. 25)

1519

Cortés arrived as conqueror in Mexico (Stuart)

1500

By this time, Southwest populations had declined to levels of the eighth and ninth centuries (Lekson, p. 189)

By this time, no vestige remained of that earlier Anasazi political world: there was no longer any central government (Lekson p. 197)

1450

Paquimé’s fall, though it could be as late as 1500 (Lekson, p. 26)

Just about everyone (in former Anasaziland) was gathered into about a hundred large towns, clustered at Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and Laguna in the Rio Grande Valley from Socorro in the south to Taos in the north — a very big change (Lekson p. 194)

After this date, dramatic decline in Pueblo towns; things grew much worse after European intrusion; more than fifty large Rio Grande pueblos were abandoned in historic times, leaving only twenty today (Lekson p. 197)

Little left of Hohokam’s earlier glories (Lekson p. 246)

Before this date in the south, ethnography has little useful to say (meaning oral stories of descendant puebloans has little value) (Lekson p. 249)

to 1500

Paquime sacked and burned sometime during this period (Lekson p. 214)

1440

Aztec king Moctezume I sent an expedition to the north to find Aztlan, the mythic source of the original Aztecs (Lekson, p. 191)

1420

Disastrous floods hit the Gila River drainage (Lekson p. 243)

1410

Arroyo Hondo declined again due to drought, burned in 1420 and abandoned by 1425 (Stuart)

1400

At the latest, Mogollon culture had disappeared (Martin p. 141)

Navajo arrive in Four Corners region (source?)

Mogollon uplands largely depopulated (Lekson, p. 24)

After this date, typical Anasazi village size jumped to more than 500 rooms … that effectively subugated the needs of the few to the will of the many (Lekson p. 195)

to 1450

A second large-scale “abandonment,” rivaling the Four Corners, emptied the southern Pueblo region — the big pueblos of the Mogollon uplands and along the toe of the Plateau (Lekson p. 1960

1386

to 1395

Decade of drought in Salt River (Hohokam) drainage (Lekson p. 206)

1384

Enormous floods along Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1382

Enormous floods along Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1381

Enormous floods along Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1375

Trafficking in Macaws ended (source?)

1370

Arroyo Hondo resettled (Stuart)

1360

to 1361

Catastrophic drought in drainage area of the Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1359

Disruptive flood along Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1358

Disruptive flood along Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1357

Disruptive flood along Salt River (Hohokam) (Lekson p. 205)

1350

Dental transfiguration noted in Guasave, Sinaloa (source?)

to 1400

Many of the Mexican cultures had collapsed (Martin p. 141)

to 1600

Pueblo IV: Large plaza-oriented pueblos; Kachina Phenomenon widespread; corrugated pottery replaced by plain utility types; black-on-white pottery declines relative to red, orange, and yellow types (Roberts from Lipe)

1345

Arroyo Hondo abandoned (Stuart)

1340

“The tree-ring reconstructions show that at 1300 to 1340 it was exceedingly wet,” said Larry Benson, a paleoclimatologist with the Arid Regions Climate Project of the United States Geological Survey. “If they’d just hung in there…” Though the rains returned, the people never did. —“Vanished: A Pueblo Mystery,” by George Johnson, April 8, 2008, The New York Times

1335

Precipitation declined around Arroyo Hondo (Stuart)

1325

First evidence of Kachina cult (Roberts p. 102; 150)

Mexican Aztec culture developed from anarchic post-Toltec culture in Central Mexico (source?)

1325 to 1350

Population of Pueblo IV people was as much as three-quarters lower than population of Anasazi around 1050 (Stuart)

1320

1320 to 1350s

On many mesas and isolated hillocks overlooking farmlands adjacent to the Rio Grande and Rio San Jose (in the Acoma area), people built thick-walled citadels (Stuart)

1310

Arroyo Hondo Pueblo, five miles south of Santa Fe at 7,100 feet, was founded; by 1330 the site was immense with more than 1,000 rooms (Stuart)

1300

There never was an “Anasazi tribe”, nor did anyone ever call themselves by that name. Anasazi is originally a Navajo word that archaeologists applied to people who farmed the Four Corners before 1300 AD. (BLM)

By this date, natural conditions (precipitation — the lack of) had forced Chacoan survivors to a few sites along rivers (Stuart)

By this date, only the best-watered east-facing canyons and slopes were still inhabited (Stuart)

Early this century, masked rain gods and the kachina cult, thought to have originated west of the Zuni area, began to penetrate the eastern pueblos and displace many older religious customs (Stuart)

Mid-century: Violence on the southern frontiers seems to have been largely sorted out, and settlements shifted downhill to the rivers’ open floodplains (Stuart)

By this time the Anasazi heartland (around modern Four Corners) was empty (Lekson, p. 23)

Cahokia was empty and derelict (Lekson, p. 152)

By this year, northern Chihuahua was one of the most densely settled areas in the southeast (compared to essentially empty at 1200) (Lekson, p. 176)

A watershed year, a demographic zenith for the Southwest, followed by catastrophic population decline, nearly complete reorganization of peoples and polities, and then centuries of colonization (by the Spanish) (Lekson, p. 189)

The Mexica, who would become the Aztecs, arrived in the Valley of Mexico from the north (Lekson, p. 191)

After this time, most Pueblo IV towns had only two or three large kivas — something happened around this time to radically change basic Anasazi house/village form (Lekson p.195)

End of migrations out of the Four Corners (Lekson p.195)

After this date until 1450, dramatic growth for Pueblo towns (Lekson p. 197)

T-shaped doors all but gone from the Plateau and Pueblo region, only to reappear throughout Paquime (Lekson p. 211)

Before this date in the north, ethnography has little useful to say (meaning oral stories of descendant puebloans has little value) (Lekson p. 249

Pueblos developed after this time as a reaction to state-level governments, conscious rejections of earlier hierarchies. They deliberately replaced the kings of Chaco with the priests of Zuni. (Lekson p. 251)

to 1500s

Galisteo basin pueblos controlled most of the turquoise trade by controlling Mount Chalchihuitl (“turquoise mountain”) in the Cerillos Hills — the Aztecs of Mexico actually had a place glyph for this mountain (Stuart)

to 1350

Population peaked across the whole Southwest, then plummeted sharply (Lekson, p. 189)

to 1340

“The tree-ring reconstructions show that at 1300 to 1340 it was exceedingly wet,” said Larry Benson, a paleoclimatologist with the Arid Regions Climate Project of the United States Geological Survey. “If they’d just hung in there…” Though the rains returned, the people never did. —“Vanished: A Pueblo Mystery,” by George Johnson, April 8, 2008, The New York Times

1295

“Fully half the Anasazi domain had been abandoned around 1295 and never reoccupied.” (Roberts p. 213)

1290

This decade, Tyuonyi, a great circular ruin in Bandelier National Monument, was founded, along nearby Frijoles Creek, a permanent stream (Stuart)

1286

Last construction date for Keet Seel (Roberts p. 105)

1285

Salmon abandoned by Mesa Verdeans (Frazier p. 135)

1280

It’s interesting that the BLM uses the word occupation. The Anasazi occupation of the Four Corners lasted until 1280. The Nazi occupation of France lasted until 1944.

The last villagers left Mesa Verde (Lekson, p. 163)

1276

to 1299

The great Chaco Canyon drought (Roberts p. 151)

The Great Drought (Lekson, p. 143)

1275

After this date, the erratic and declining rainfall turned into a series of deep, localized droughts (Stuart)

Even worse drought hit Anasazi region and violence spun out of control (Lekson p. 239)

1275

To enforce its failing rule [after yet another drought began in 1275], Aztec unleashed lethal force. At farmsteads, squads of warriors fell upon families failing in their duties, old and young. They were executed to intimidate other villages that might be thinking of slipping Aztec’s yoke. Men, women, and children were brutally and publicly killed and left to rot, unburied, in the ruins of their homes. These horrible scenes replayed a score or more times, but even terror could not hold Aztec’s failing polity together. —A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson, p. 239. Image of Anasazi warriors from a website with no clear name displaying a Reproduction by Thomas Baker of an Anasazi Indian kiva mural unearthed at Pottery Mound, New Mexico.

1275 to 1300

The Great Drought brought Sinagua to collapse (source?)

1270

By this year, Aztec West’s Chaco-sized rooms had been subdivided into tiny unit pueblo rooms, and family “kivas” had been jamed into adjacent Chaco chambers (Lekson, p. 160)

1267

1267 to 1286

Construction of Betatakin (Roberts p. 96)

1263

Most Mesa Verdeans leave Salmon (Frazier p. 135)

1260

Drought struck again with a vengeance (Stuart)

Mesa Verdeans moved into Salmon this decade (source?)

1260 to 1270

Farmers on west-facing slopes were hardest hit by drought, while those on east-facing slopes survived (Stuart)

1259

A major volcanic eruption somewhere outside the Southwest dropped temperatures (Lekson, p. 162)

1253

1253 to 1284

Mummy Cave constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1250

After this time, precipitation became more erratic (Stuart)

By this decade, trade across the region increased (Stuart)

“Around 1250, you see an incredible change. Everybody’s moving into the canyons, building cliff dwellings. At Sand Canyon, 75% of the community lived within a defensive wall that surrounded the pueblo. All through southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, southwestern Colorado, the same thing’s happening. Suddenly, at 1250, the trade ware goes to zero. Before that, you had plenty of far-traded pottery, turquoise, shells, jewelry. Suddenly, nothing. And right at 1250, the ceramics revert from Mesa Verde-style pitches–tall, conical vessels with rounded bulblike bases–to the kinds of mugs made at Chaco 200 years earlier.” (Roberts from Bruce Bradley of Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, p. 150-151)

Construction start date for Keet Seel (Roberts p. 105)

A general breakdown in annual predictability of precipitation made farming increasingly chancy (Lekson, p. 162)

Paquimé rose to prominence (Lekson, p. 172)

After this year, platforms became elite residences (Lekson p. 202)

In the decades after this time, Chacoan ruling families were looking for someone to rule. Hohokam needed leaders and the Platueau had a surplus (Lekson p.203)

1250 to 1500

Casas Grandes in northern Mexico as center of Chacoan culture (Frazier p. 234, from Lekson)

1250 to 1450

Great migrations shifted tens of thousands of people acros the region, shaping a new Southwest (Lekson, p. 190)

1250 to 1325

All across the Pueblo world, from Hopi to the Rio Grande, population increased, doubtless from relocations from the Four Corners (Lekson p. 197)

1250 to 1450

Hohokam towns spread over large areas, prefiguring the urban sprawl of modern Phoenix (Lekson p. 210)

1230

1230 to 1240

This decade, Anasazi society regrouped and aggregated into sites in the northern Rio Grande, typically at 6,600 to 7,300 feet in elevation; all were built to withstand attack; some were attacked, leaving much evidence of violence such as skulls caved in my hard blows and burning, but no looting of valuables, suggesting an attempt to drive them away or rid the country of the people (Stuart)

1230 to 1260

Large new pueblos such as Bayo Canyon Ruin near Los Alamos were constructed on hundreds of mesa tops through the Southwest (Stuart)

1223

Mean date of pit house communities (average six pit houses) in eastern Arizona, Taos, Santa Fe district, Apache Creek [?], Cebolleta Mesa [?], and in the Sierra Blanca near Ruidoso, NM; evidence of pottery trade is substantial, with more than a dozen types at many locations (Stuart)

1220

Villages began leaving the stressed sphere around Aztec Ruins (Lekson p. 239)

1216

1216 and 1262

Spruce Tree House at Mesa Verde constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1204

Square Tower House at Mesa Verde constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1200

Early this century, trade was reestablished across the four-corners region (Stuart)

Mesa Verdeans cliff houses flourished this century (Stuart)

Most skeletons from this century are marked by evidence of overwork and an inconsistent food supply (Stuart)

Or perhaps as early as 1125, Chaco Canyon culture had collapsed (Roberts p. 161)

Rock art depictions in Four Corners region of the feathered serpent, or Quetzalcoatl (aka Xipe Totec to Toltecs; aka Maasaw to modern Hopi)

Before this time, Anasazi villages were almost always small and short-lived, with the important exception of Chaco Canyon (Lekson, p. 137)

By this year, the arc of Pueblos — Hope in the west through Zuni and Acoma to the norther Rio Grande on the east, was well settled (Lekson, p. 163)

1200 to 1230

Known as the Little Ice Age in Europe; it probably got colder and wetter in the American Southwest as well (Stuart)

1200 to 1250

Precipitation increased in quantity and reliability enough to provide some surpluses of food supply (Stuart)

1200 to 1300

Late Pueblo III; Mesa Verde Phase; Pots: Mesa Verde black-on-white, indented corrugated (rock & sherd); major re-population (Tom Windes)

Mogollon culture begins moving into the Hopi-Zuni region (Martin, p 21)

Tens of thousands of Anasazi left, never to return (Lekson, p. 162)

1190

1190 to 1206

Balcony House at Mesa Verde constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1190 to 1260

Construction of all of the cliff dwellings including Mesa Verde, Bandelier National Monument, Gallina highlands, Chuska Mountains, Montezuma Castle, Mavajo National Monument in Arizona, and Gila Cliff Dwellings in Mogollon country; most were inhabited less than 100 years (Stuart)

1185

Salmon reoccupied by Mesa Verde people (Frazier p. 135)

1170

By this decade, the Chaco culture was but a memory (Stuart)

Civil war resulted in fall of Tula, capital of the Toltecs, followed by anarchy

Fighting abated in the highland regions around Chaco Canyon this decade (Stuart)

This decade, small pueblos founded at higher elevations with no sign of palisades or defensive measures, none built on cliffs; fewer had kivas; mineral-based paint on pottery replaced by organic paint from burnt plant material (Stuart)

1168

The Toltec capital Tula was destroyed by successive new tribes of barbarians coming from the north, among them the Aztecs (Waters p. 117)

1150

Aztec abandoned (Frazier p. 131)

Many Hohokam sites abandoned and relocated, about the time platform mounds replaced ball courts (Lekson, p. 23)

Many Mogollon districts abandoned (Lekson, p. 24)

Hohokam crashed (Lekson, p. 80)

No ball courts (Hohokam) were built after this time

T-shaped doors first appeared at Chaco Great Houses, but not commoner dwellings) (Lekson p. 211)

After this date, T-shaped doors showed up at Aztec Ruins (Lekson p. 211)

Hohokam ball courts replaces by platform mounds (Lekson p. 240)

After this time, everything sagged south, with migrations out of the northern Plateau bumping people of the southern Plateau farther south into the Mogollon uplands (Lekson p. 241)

This year, give or take a decade, was a rough one for North America — Tula fell, Cahokia and Chaco crashed, and Hohokam fell apart (Lekson, p. 150)

Tula [Toltecs] fell about 1150. [W]ith Tula’s end, the Post-Classic pattern came into focus in vibrant clarity: expansive politics, long-distance dynamics, power plays and upheavals, and a swirling world of migrations, invasions, expulsions, and fragmentation. —Lekson p. 242

1150 to 1300

The events of 1150 to 1300 [spelled] the end of Tula [Toltecs] and consequent regional reorganization marked by audacious long-distance trade and flamboyant political adventures. —Lekson p. 144

1150 to 1200

Wars of attrition and atrocities spread across the Chacoan world (Stuart)

1150 to 1300

A number of architectural features appeared in the San Juan Basin with clear Mexican derivation, such as triple-walled towers

The end of Tula (Toltecs) and consequent regional reorganization marked by audacious lang-distance trade and flamboyant political adventures (Lekson, p. 144)

Hohokam suffered destructive and sporadic floods about once per generation (Lekson, p. 167)

1150 to 1350

Pueblo III: Large pueblos; cliff dwellings; towers; corrugated gray and elaborate black-on-white pottery, plus red or orange pottery in some areas; abandonment of the Four Corners by 1300 (Roberts from Lipe)

1150 to 1200

Cahokia fell gradually (Lekson, p. 115)

Cahokia rose and began a precipitous decline (Lekson, p. 152)

1145

Construction began at the Wupatki Great House, perhaps as a rival to the northern San Juan, especially Aztec Ruins (Lekson, p. 157)

1140

Drought had lasted greater part of a decade, and the collapse of the Chacoan system was underway (Frazier p. 205)

Charoan roads had no historical precedent and were never re-used after the Chaco peak & fall of 1140 AD

The Chaco phenomenon had ended (Stuart)

This decade, Escalante Ruin was abandoned (Stuart)

1140 to 1200

Pueblo III; McElmo Phase; Pots: McElmo, indented corrugated (rock/sherd/sand); major de-population and severe drought (Tom Windes)

1140 to 1180

Between 1140 and 1180 AD, nine out of every ten skeletons found around the Mesa Verde region in Colorado show signs of violent injury.

1139

Last known construction at Salmon (Frazier p. 205, although it’s written as “1239,” which I believe is a typo)

The last roof bean was cut and raised at Bis sa’ani, 20 miles north of Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

1135

Wupatki built (Lekson p. 238)

1135 to 1180

Major drought hit Anasazi region (Lekson p. 239)

1133

Temporary relief from sharp drought (Frazier p. 205)

1133 to 1135

Cliff dwellings in Grand Gulch, Utah, constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1132

The last-known tree-cutting in Chaco Canyon at Pueblo Alto (Frazier p. 205)

1130

## women and children were burned to death in the tower kiva.

Founded just before 1100, Salmon was a Chacoan refuge until a number of its women and children were burned in the tower kiva that once arose from the main block. —Anasazi America, by David E. Stuart, p. 105. It was apparently attacked and more than 30 women and children who had sought refuge in its impressive tower kiva died horribly in a fire set to destroy the town [in about 1130]. —Anasazi America, by David E. Stuart, p. 136. Aerial view of Salmon Ruins from The Foxworthy Traveling Show.

After the drought of this year, tens of thousands of farmers and others displaced from shrinking great houses and fled to the uplands, including Chuska and Lukachukai mountains to the west, Mesa Verde and San Juan ranges on the north, Gallina highlands on the east, the foothills of Albuquerque’s Sandia and Manzano mountains on the southeast, and Cebolleta Mesa, the El Morro district, and the Zuni Mountains to the south [odd, then, that CR was abandoned this same year] (Stuart)

Beginning of severe drought that lasted 50 years (Frazier p. 205)

Doyel proposes that a prolonged and severe drought brought more than 250 years of Chacoesque development to an end

Fifth and last major construction period for Pueblo Bonito (Frazier p. 77)

Salmon abandoned; it was apparently attacked and more than 30 women and children who sought refuge in its impressive tower kiva died horribly in the fire set to destroy the town (Stuart)

The Chacoan elites who held on in a half-dozen of the more stable great houses after this year lost access to nearly all their signature trade goods: corn surplus; dried meat; etc. [turquoise?] (Stuart)

The second Chaco drought was the coup de grace that brought the Chacoan culture down (Stuart)

Pochteca, “long-distance traders and spies who hailed from Aztec Mexico…we know them only from an era well after the AD 1300 abandonment, [though] they serve as a powerful model for hypothesized earlier traders who may have brought Mesoamerican ideas to the American Southwest, particularly Chaco Canyon.” (Roberts, p. 170)

Mimbres ended — at 1100 there were five to ten thousand people living in Mimbres towns throughout southwestern New Mexico; by 1150 there weren’t any (Lekson, p. 174)

When Chaco’s move to Aztec Ruins was complete, Mimbres region emptied (Lekson p. 241)

1130 to 1140

This decade, Bis sa’ani was built, perhaps to protect the central Chaco Canyon from unrest among the Chacoan northern farming communities (Stuart)

1130 to 1135

Chimney Rock abandoned

1130 to 1150s

Fighting peaked in the highland regions around Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

1130 to 1180

Prolonged drought with precipitation below normal — coincides with gradual abandonment of Chaco (Frazier p. 181, from Judge)

Yet another great drought (Lekson, p. 154)

During the drought, unspeakable violence came out of Aztec, marked by brutality and cannibalism (Lekson, p. 160)

1127

Pueblo Bonito was “still” occupied (Frazier, p. 76)

1125

“The richest burial ever reported in the Southwest,” as described by John McGregor, at Ridge Ruin near Flagstaff, Arizona (Roberts p. 219)

Ida Jean great house established (Stuart)

Kin Kletso construction began and continued through 1130 (NPS.gov)

Wallace great house established (Stuart)

After this date, the Anasazi center of gravity and gravitas shifted north, from Chaco Canyon to Aztec Ruins (Lekson, p. 153)

Construction at Chaco Canyon declined sharply and ceased by this year — just before the nasty drought of 1130-1180 (Lekson, p. 156)

1125 to 1129

Escalante great house established (Stuart)

1120

By this date, there was more than 100,000 square meters of floor area under roof in Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

Chetro Ketl abandoned (Frazier p. 79)

Final Aztec construction (Frazier p. 131)

This decade Mesa Verde region Chacoan-style communities were constructed: Ida Jean, Wallace, Escalante Ruin, each at 6,300 feet elevation or greater; probably founded by groups of male colonists (Stuart)

1120 to 1140

No Chacoan great kivas constructed (Stuart)

1120 to 1140s

Escalante Ruin was constructed, including one large kiva, in southwest Colorado at 7,200 feet (Stuart)

1116

Eerily, [Salmon Ruin’s] last roof beams were repaired and replaced at A.D. 1116, the same year repair and expansion stopped in most great houses within the canyon. —Anasazi America, by David E. Stuart, p. 84. Image of roof beams from Aztec Ruins, not Salmon, fromThe Foxworthy Traveling Show.

End of minor refurbishing at Salmon (Frazier p. 135)

Last Chetro Ketl beam cut (Frazier p. 79)

Salmon ruin: Exodus begins; Rex Adams said, “rather dramatic internal modifications, such as the sealing of doors and the deposition of trash in the ground floor of many rooms began.” Final abandonment “was rather abrupt.” (Frazier p. 135)

The last roof beams cut and put in place at Salmon (Stuart)

1116 to 1120

Most construction in the canyon itself stopped between 1116 and 1120, and some older great houses such as Chetro Ketl were actually being abandoned. But at others, as at Pueblo Bonito, new walls and room blocks were built to close off old courtyards and limit access. —Page 121 (Stuart)

1115

Aztec constructed (Stuart)

Most Aztec construction ends (Frazier p. 131)

Spring House at Mesa Verde constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1115 to 1140

Signs of significant reorganization of Chaco culture: most construction during this period took place at sites north of Chaco Canyon (Frazier p. 203)

1112

Oak Tree House at Mesa Verde constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1111

New great houses were established at Aztec (A.D. 1111-1116, expanded in the 1200s),Escalante (1125-1129), Ida Jean (about 1125), and Wallace (about 1125), all north of the San Juan River…where good water, uncrowded conditions, and upland game were available. —Anasazi America, by David E. Stuart, p. 120-121.

1111 to 1116

Aztec great house established, expanded again in the 1200s (Stuart)

1110

Chaco ended about 1125 and rose again 60 kilometers due north at Aztec, where major construction began about 1110. That was the final outcome, but there may have been a false start or two. —A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson, p. 154

The Great North Road line was extended north [about 10 miles] from Salmon to a stream of more appropriate size, the Animas River. Construction started on Aztec Ruins about 1110. —A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson, p. 154. Photo of Aztec Ruinsfrom ImagesOfAnthropology.com.

Main Aztec, New Mexico, construction begins (Frazier p. 131)

Major construction began at Aztec Ruins (Lekson, p. 154) in a solsticial orientation (Lekson, p. 155)

Construction began at Aztec Ruins (Lekson p. 238)

1110 to 1121

Beams cut for Aztec Ruin (Frazier p. 77)

1110 to 1275

Aztec as center of Chacoan culture (Frazier p. 234, from Lekson)

1102

Fourth major construction period for Pueblo Bonito (Frazier p. 77)

1101

1101 to 1104

Windes claims this was tree-harvesting dates for Pueblo del Arroyo — after last was cut, they were moved into the canyon and building began (Frazier p. 227, from Windes)

1101 to 1105

North and south wings, plaza, and the tri-walled structure were added to Pueblo del Arroyo (NPS.gov)

1100

Most of the later and so-called higher developments of the Anasazi came to them from the Hohokam and Mogollon groups, so that the climax that occurred about A.D. 1100 may be regarded as an accumulations of southern and possibly Mexican traits that were taken over by the Anasazi bit by bit—by trade, by drift, perhaps by war—and reworked to fit their ideas and cultural layout. (Martin p. 20)

Large religious gatherings did not take place in Chaco Canyon after 1100. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 143

All of this evidence of violence dates to the 1100s. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 121

Representations of masked dancers appear on Mogollon pottery (Martin p. 131)

Small copper trinkets, probably imported from Mexico, found in some Mogollon sites after this date (Martin p. 77)

After this date, large religious gatherings did not take place in Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

By this date there were nine great houses in Chaco Canyon: Peñasco Blanco, Casa Chiquita, Kin Kletso, Pueblo del Arroyo, Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, Hungo Pavi, Una Vida, and Wijiji; plus three up on the mesa: Pueblo Alto, New Alto, and Tsinkletzin (Stuart)

By this time, most of the great houses in the southern San Juan basic were abandoned (Stuart)

During the early part of this century, Chaco’s great houses walled their courtyards and built control gates where roadways passed village walls (Stuart)

Early this century, Wijiji constructed (NPS.gov)

Early this century evidence of violence abounds in and around Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

Early this century, a pit-house community in Gallina was laboriously stockaded, from fear of the invading Chacoan farmers; many such sites exist, all of which have been breached and burned (Stuart)

Early this century: An estimated 60 percent of adults and 38 percent of children died violently in the Gallina highlands after the collapse of Chacoan society (Stuart)

Early-to-mid-century: Kin ya’a (south of Chaco Canyon) was burned and abandoned (Stuart)

Huge explosion in number of kivas built (Stuart)

Kin ya’a was expanded (Stuart)

Peak population of Chacoans during early part of this decade (Frazier p. 91)

The center of Chaco culture shifted to near the banks of the San Juan River, north of Chaco Canyon the first few decades of this century (Stuart)

The middle of this century, Navajo people invaded Chacoan territory — perhaps the cause of the fear that made Chacoans build defensive structures and cliff dwellings (Stuart)

There are 3,200 known sites dated to this decade, a ninefold increase from 500 years before (Stuart)

Trafficking in Macaws began (presumably out of Mexico and into Four Corners area) — what’s the source on this? I propose Macaw feathers appeared long before this; need to double-check this one, or ignore it

Numic tribes (Utes, Paiutes, Shoshone–linguistic roots of the modern Hopi language) were in the Great Basin of Nevada as early as this date (Roberts p. 204, 205)

Pueblo towns such as Oraibi and Acoma began, perhaps even sooner (Lekson, p. 20)

Pueblo Bonito, originally build in the 900s with a solstitial alignment, changed and adopted Pueblo Alto’s consciously cardinal orientation (Lekson, p. 127)

By this time, a few score elite Chacoan elite families (Lekson p. 236)

1100 to 1130

Chaco rainfall in excess of normal (Frazier p. 203)

1100 to 1190

Most pit house communities were constructed and occupied in the highlands surrounding Chaco Canyon, most probably with farmers dispersed from the Red Mesa Valley and other areas sound of Chaco; most of these [if not all] were attacked and burned (Stuart)

1100 to 1300

Grand Gulch on Cedar Mesa in Utah inhabited again, the cliff dwellings were built, then abandoned (Roberts p. 131)

1100 to 1200s

Chaco had a central government that sanctioned violence in the 1100’s

Chaco…had a central government, however diffuse or non-Western…. It’s likely that Chaco had a regional economy. And perhaps Chaco and its successor, Aztec Ruins [in northern New Mexico], had the use of force; witness the brutality of apparently socially sanctioned events of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. —Lekson p. 223

Hovenweep built, including tower with slits for sunlight that describes a complete solar calendar (Frazier p. 199)

1100 to 1200

Cahokia Creek split in two, spelling its ultimate doom (Mann p. 296)

1099

1099 to 1116

Chetro Ketl architecture degenerated; poor workmanship (Frazier p. 78)

1098

Full moon on the summer solstice, June 15, 1098. (Equinox & Solstice Calculator and Moon Page)

1095

1095 to 1100

MAJOR construction at chacoan pueblos.

[Stephen] Lekson divided the construction activity into five-year segments and found that the last five years of the eleventh century, A.D. 1095-1100, were the most labor intensive. During those five years, Chacoan construction programs took up an average of 55,645 man-hours, or 5,565 man-days, or 186 man-months, per year. Thus thirty-one men working six months a year or sixty-two men working three months a year could have carried out the most intensive single period of construction at Chaco Canyon. —Page 179 (

Frazier)

1094

Lunar standstill and, some claim, second wave of building at Chimney Rock Great House (building perhaps began in 1093) (Frazier p. 222)

Salmon mostly completed

Second building phase at Chimney Rock (Roberts p. 217)

1094 to 1104

Minor construction and finishing work at Salmon (Frazier p. 135)

1093

26 wood samples from Chimney Rock Great House were cut in this year; also five samples from rebuilt East Kiva match this year

Last wave of trees cut for Salmon construction (Frazier p. 135)

1090

Chaco’s shift to the north began four decades before an 1130-1180 drought, often blamed for Chaco’s demise. —A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson, p. 154

A drought began that lasted five or six years (Stuart)

Drought, no summer rains for six years (Stuart)

Sharp drought this decade (Frazier p. 203)

Major construction began on the Salmon Ruins Great House (Lekson, p. 154)

1090 to 1140

Early Pueblo III; Late Bonito Phase; Pots: Chaco-McElmo/Gallup b/w, indented corrugated (sand); Major great-house construction north of San Juan River; Major population increase, then decrease (Tom Windes)

1090 to 1100

Proposed dates for pollen from the fill of a Chimney Rock indigenous hearth on Chimney Rock lower mesa

1090 to 1115

Pueblo Bonito was “finished” to look much as it does today, including the addition of 14 new kivas (Stuart)

1090 to 1116

The third and final wave of great-house construction in Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

1088

Salmon ruin was mostly built as one massive project between A.D. 1088 and 1090. The great house was constructed in the shape of a square C. Its back (north) wall is 450 feet long. The two arms of the C, each 200 feet long, reach south toward the Great North Road from Chaco. The great house once stood two to four stories tall, contained at least 175 rooms, and had a floor area of 90,000 square feet—nearly two acres… [I]t was built in the midst of the worst drought since the rains had become more favorable 90 years before. —Anasazi America, by David E. Stuart, p. 83. Image of Salmon Ruins from TripAdvisor.com.

1088 to 1090

Most trees cut for Salmon [great house] construction (Frazier p. 135)

Salmon [great house] was constructed as one massive project (Stuart)

1087

Tree-ring date of a partially burned branch from a domestic fire pit in an indigenous house on Chimney Rock lower mesa

1085

1085 to 1110

Windes concludes 18 households living in Pueblo Bonito; Hayes estimates 179 families (Frazier p. 157)

1080

Summer rainfall had begun to decline noticeably (Stuart)

Chaco got drier, but the drought had surprisingly little effect on building (Lekson, p. 155)

1080 to 1100

Casamero in Red Mesa district was constructed, perhaps as a last-ditch effort to hold the area together (Stuart)

Chacoans built four-story tower kivas at great expense of labor and materials (Stuart)

1079

Full moon on the summer solstice, June 16, 1079. (Equinox & Solstice Calculator and Moon Page)

1077

1077 to 1081

Widespread building at Pueblo Bonito (Frazier p. 231, from Windes)

1076

Lunar standstill and, some claim, first building at Chimney Rock Great House (Frazier p. 222)

Tree-ring date of one cross pole from ventilator shaft of Chimney Rock East Kiva; Eddy accepts this as date of building, most others suspect this is an older re-used timber

1075

After this date it appears that rooms at larger sites were no longer used for living or storage, but for possible ceremonial functions (Frazier p. 185, from Judge)

By 1075, at the latest, Hohokam had begun to unravel [just as] Chaco burst forth to dominate the Plateu from 1020 to 1125. (Lekson p. 234)

First building phase at Chimney Rock (Roberts p. 217)

New foundations laid at Pueblo Bonito that were never completed (Stuart)

Pueblo del Arroyo construction began in the central portion (NPS.gov)

Hohokam really fell apart (Lekson, p. 116)

Things around Phoenix (for Hohokam) began to detriote — ball courts were abandoned and platforms were built over mounds (Lekson p. 203)

1075 to 1115

Around A.D. 1075 the Chacoans began an unparalleled flurry of building activity that would last forty years…. From then until 1115 the Chacoans carried out six major construction programs in Chaco Canyon. They built the east and west wings of Pueblo Bonito. —Page 177 (Frazier)

1075 to 1130

Fourth Chaco building period: major building period: east and west wings of Pueblo Bonito, added third story to Penasco Blanco, north and south wings of Pueblo del Arroyo, constructed Wijiji — yearly levels of labor were twice that of 1050 to 1075 (Frazier p. 174+, from Lekson)

1073

Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1070

26 of 53 wood samples from small, down-slope Chimney Rock sites give dates in this decade; only 2 of 47 samples from Great House from this decade

After this date only Type III masonry used at Chetro Ketl (Frazier p. 78)

Hohokam ball court networks were in serious decline if not total collapse (Lekson, p. 121)

About the time of the Sunset Crater volcanic explosion? (Lekson p. 238)

1068

Salmon Ruins was as large as the largest construction at Chaco Canyon. It was not a casual experiment.

After the initial four-room unit [started in 1068], there was nothing tentative about the move. Salmon Ruins was as large as the largest individual construction events at Chaco Canyon. This was not a casual experiment. —A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson, p. 154.

Salmon Ruins’ east wing was built as early as 1068. About 1090 major construction began on the actual Great House, a building the size and shape of Hungo Pavi back at Chaco Canyon. —A History of the Ancient Southwest, by Stephen H. Lekson, p. 154. Diagram of Salmon Ruins from University of Idaho.

A four-room unit was the first built at Salmon Ruins (Lekson, p. 154)

1067

Pueblo Bonito’s “golden age” (Frazier p. 76)

1066

Vingta born (The Last Skywatcher Series)

March 20, 1066

Halley’s Comet appeared (Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halley’s_Comet)

1063

Sunset Crater exploded after this year, covering the Sinagua area with a thin layer of “black sand” (Lekson, p. 76, citing Colton)

1062

First use of Type III masonry at Chetro Ketl

1092 to 1070

Both Types II and III masonry used at Chetro Ketl

1060

1060 to 1061

Pueblo Pintado was built as one planned project (Stuart)

1060 to 1065

Pueblo Bonito enlarged again, mainly with the addition of stories (Stuart)

1060 to 1090

Major remodeling and rebuilding of Chetro Ketl (Frazier p. 78)

1060 to 1096, 1219, 1275

White House Ruin in Canyon de Chelley constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1057

Date of The Last Skywatcher, prequel novel to The Last Skywatcher Series

Lunar standstill (Frazier p. 222)

Full moons in 1057 (www.moonpage.com): January 23, February 22, March 23, April 22, May 21, June 19 (four days after the Summer Solstice), July 18, August 17, September 15 (two days before the Fall Equinox), October 15, November 14, December 13 (two dates before the Winter Solstice)

Solar dates in 1057 (Equinox and Solstice Calculator): Spring Equinox, March 14; Summer Solstice, June 15; Fall Equinox, September 17; Winter Solstice, December 15

Which dates would they watch the lunar standstill through the Chimney Rock twin towers? This illuminates (and surprises), from http://www.idialstars.com/mls.htm:

A major (or minor) lunar standstill always happens near an equinox; and what’s more, it happens when the Moon is at or near quarter phase. A major lunar standstill faithfully occurs within one week of a lunar or solar eclipse, and oftentimes takes place right between a lunar and solar eclipse.

This implies that the most likely date to watch a full moon rise between the twin spires of Chimney Rock National Monument, Colorado, closest to its standstill in 1057, is September 15.

1054

July 4

Crab Nebula Supernova “first observed on 4 July 1054, and that lasted for a period of around two years. The event was recorded in contemporary Chinese astronomy, and references to it are also found in a later (13th-century) Japanese document, and in a document from the Arab world. Furthermore, there are a number of proposed, but doubtful, references from European sources recorded in the 15th century, and perhaps a pictograph associated with the Anasazi Pueblo Peoples found near the Peñasco Blanco site in New Mexico.” (Wikipedia article on SN 1054) Also “Around 4-5 July 1054 the supernova was visible in broad daylight, having reached a maximum brightness about ten times that of Venus, the brightest astronomical object visible from Earth besides the Sun and Moon. It remained visible by day for 23 days, and by night for 653 days.” (Solar Astronomy in the Prehistoric Southwest on the The National Center for Atmospheric Research site)

1053

to 1103

Pueblo del Arroyo, just across the wash from Pueblo bonito, constructed (Frazier p. 77)

1050

In many cases, Chaco elites were sometimes able to co-opt Great Kivas. The largest Great Kiva of its age was built within the walled plaza of Pueblo Bonito—the first and greatest Great House—about 1050. (Lekson p. 235)

A third masonry-lined kiva was added to site 627 (Stuart)

After this date, Chacoan farmers began moving into the northern San Juan basin with few, if any, underlying Basketmater or Pueblo I houses (Stuart)

After this date, formal roadways were constructed from Chaco Canyon to the most architecturally complex buildings to the south (Kin ya’a, Casameo, etc.) (Stuart)

Basic structure of Chaco System was in place (Frazier p. 185, from Judge)

By this decade, the Chaco culture was three-tiered: farmsteads, district great houses, and Chaco Canyon great houses (Stuart)

Hohokam took a downturn (Lekson, p. 116)

to 1060

Wing additions to Pueblo Bonito (Stuart)

to 1075

Construction during the third period, 1050 to 1075, was mainly of additions to existing buildings. The Chacoan builders added wings, then less symmetrical additions, extensions and modifications. More [labor hours of] construction work was being done each year. —Page 176 (Frazier)

The second wave of great-house construction in Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

Third Chaco building period: mainly additions to existing buildings; only one new structure: Pueblo del Arroyo (Frazier p. 174+, from Lekson)

to 1080

New farming districts opened to the north of Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

to 1100

Road networks built round Chaco (Frazier p. 187, from Judge)

Sunset Crater erupted sometime between these years, the first eruption in the Southwest in more than a thousand years (Lekson, p. 156)

At its peak, A.D. 1050 to 1100, Cahokia may have been home to as many as 15,000 people. Monks Mound, the largest earthwork in North America at 100 feet tall, may have been constructed in only 20 years. More here: “Cahokia’s Monks Mound May Have Been Built in Only 20 Years” on ArchaeologicalConservancy.org.

to 1115

Judge argues that formal pilgrimages to Chaco were in place by this time (Frazier p. 186)

to 1125

At least three Chaco-style remodeling events took place between these years at Guadalupe Ruin (Frazier p. 145)

to 1130

Chaco precipitation was generally above normal, except for sharp drought in the early 1090s (Frazier p. 181, from Judge)

to 1075

Hohokam sites were depopulated (Lekson, p. 116)

1041

Tuwa born, a primary character in The Last Skywatcher Series

1041

Only tree-ring date available for Casamero (Stuart)

1040

This decade, only major Chacoan building period not linked to wetter than normal conditions; construction integrates Pueblo Bonito, Pueblo Alto, and Chetro Ketl with the great roads; Windes suggests this signifies Chaco Canyon’s emergence as a regional center (Frazier p. 231)

to 1080

Pueblo Bonito construction included only 10 rooms with hearths (Frazier p. 157)

to 1100

Late Pueblo II; Classic Bonito Phase; Pots: Gallup b/w, indented corrugated (sand & trachyte); Major greathouse construction; Major depopulation, varied climate, drought, major crop surplus (Tom Windes)

1038

Lunar standstill (calculated by me)

1033

to 1092

Third major construction period for Pueblo Bonito (Frazier p. 77)

1030

to 1070

Chetro Ketl Type II masonry (Frazier p. 78)

to 1090

Second Chetro Ketl construction and occupation — marked by rapid growth; Type II masonry (Frazier p. 78)

to 1300s

Pueblo III culture (Frazier p. 81)

1020

By this decade, the Chaco culture was two-tiered: farmers and those in charge of food storage and ritual (Stuart)

Chetro Ketl construction began, with modifications in the 1100s (NPS.gov)

Elite families flourished on the Chacoan Plateau (Lekson, p. 129)

Construction at Chaco Canyon added wings of warehouses, ritual spaces, public monuments, and barracks (at least group houseing) (Lekson p. 235)

to 1040

The great expansion of Pueblo Bonito, which added two stories of rear rooms and great thickness to the outer rear wall (Stuart)

to 1050

Chaco cornered the turquoise trade (Frazier p. 183, from Judge)

Chacoan world became much more complex, with rise of elite class and expansion of lower farming class (Stuart)

land use and settlement patterns changed rapidly in Chaco Canyon, with great-house expansions that made them enormous (Stuart)

The next major construction, from 1020 to 1050, was at Pueblo Alto, Chetro Ketl, and Pueblo Bonito (additions). The architectural forms begun in the 900s were continued. —Page 176 (Frazier) See Author Note The Anasazi Buildings of Chaco Canyon: Largest “Apartments” in the World.

The first wave of great-house construction in Chaco Canyon (Stuart)

to 1080

Formal Chacoan great houses in the southern San Juan basin were invariably established well after the farms were founded (as opposed to great houses of the north, which were not) (Stuart)

to 1120

More than 2 million man-hours of labor went into the great houses in Chaco Caynon, including an estimated 215,000 ponderosa trunks up to 30 feet long each cut by stone ax and carried 20 to 30 miles (Stuart) [Note: This is 384 hours per week all year long for 100 years, which is about 9 men working 40-hour weeks every week every year for 100 years.]

to 1125

Building boom of Chacoan Great Houses (Lekson, p. 123)

to 1130

the period generally referred to as the Chaco Phenomenon

to 1125

Chaco burst forth to dominate the Plateau (Lekson p. 234)

1019

Lunar standstill (calculated by me)

1018

Lunar standstill as reported by Chimney Rock National Monument, Colorado, website

1017

Second major construction year for Pueblo Bonito (Frazier p. 77)

1001

Lunar standstill (calculated by me)

1000

Probably light settlement of Stollsteimer Valley below Chimney Rock began

Mogollon designs on Mimbres pottery became increasingly complex, better, and more delicately executed (Martin, p. 116)

Mogollon towns after this began to break up into new separate units and move a short distance away (Martin p. 90)

The tribute-demanding and militaristic theocracy of the Toltec culture began to collapse

Mogollon before this year characterized by brownware pottery made by coiling and pit houses; after this year pueblos of stone or adobe and farming

Mogollon prior to this year were very cozy with Hohokam (Lekson, p. 64)

Mimbres architecture became more like Anasazi unit pueblos from pithouses (Lekson, p. 94)

The final demise of the West Mexican Teuchitlan polities (Lekson, p. 114)

Substantial Anasazi populations migrated into the Mogollon Rim country of Arizon and into the Mogollon highlands of west-central New Mexico (Lekson, p. 136)

to 1020

Chaco firmly established as the primary source of finished turquoise for perhaps entire San Juan Basin (Frazier p. 183, from Judge)

to 1050

Additions and improvement at site 627, including renovation of two pit houses into kivas (Stuart)

to 1100

Pueblo II; Early/Classic Bonito; Kivas appear (Tom Windes)

to 1115

Chetro Ketl was built (Stuart)

to 1130

Midsummer rains came more predictably, with only one interruption in the 1090s (Stuart)

994

to 1084

Range of tree-ring dates for Chimney Rock Great Kiva (below Great House on mesa)

990

to 1102

Northern San Juan effectively empty; Pueblo I in Chaco (Lekson, p. 99)

987

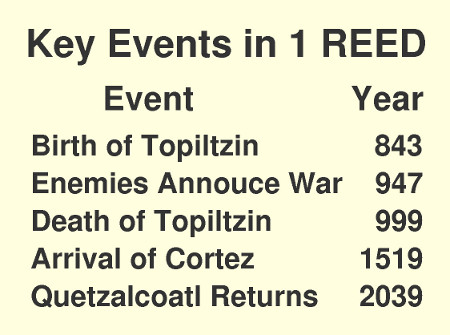

Toltec King Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl ousted for political reasons from kingdom were Mexico City is now (Mann p. 27)

982

Lunar standstill (calculated by me)

980

to 990s

Food shortages and starvation among Chaco farming communities (Stuart)

964

Lunar standstill (calculated by me)

950

By this time there were densely packed farming communities of unit pueblos on every ridge and hillock in the Red Mesa Valley (near Gallup, NM), Skunk Springs, and the Chuska Valley (Stuart)

Chaco people began building surface structures seemingly derived from Mexican culture (such as what?)

The Late Pithouse Period (Mogollon) ended with a shift from pit structures to pueblo-style architecture (Lekson, p. 92)

Turner identifies 11 cannibalized skeletons at Burnt Mesa in northwestern NM (Roberts p. 158)

to 1000

Rooms added to site 627 (Stuart)

All masonry house blocks around Kin ya’a (south of Chaco Canyon) were built (Stuart)

to 1150

Chaco Canyon boomed expansively, then collapsed (Lekson, p. 69)

to 1250

Cahokia, Mississippi, at its height. (Mann p. 291)

945

to 1030

Chetro Ketl construction and occupation — Type I masonry (Frazier p. 78)

936

to 957

Sliding Ruin in Chinle area of Navajo Reservation in Arizona constructed (Frazier p. 77)

930

to 960

Una Vida underwent expansions (Stuart)

920

to 925

The earliest construction at Pueblo Bonito, in which 17 rooms had hearths (Frazier p. 157)

919

First year of construction for Pueblo Bonito

Oldest beam cut for Pueblo Bonito (from a tree that was 219 years old when cut) (Frazier p. 76)

900

Chacoans began construction in the early 900s at Penasco Blanco, Pueblo Bonito, and Una Vida…. They gave them all remarkable similar floor plans. They created a line of large circular pit structures in the plaza. Behind them they build a row of large ramada-living rooms, a second row of large featureless rooms, and in the rear, a third row of smaller storage rooms. They formed above-ground rectangular rooms into suites, each of which consisted of a ramada-living room, a large room, and paired storage rooms. This pattern of rooms is remarkably similar to smaller sites built in Chaco and in the surrounding area at the same time. —Pages 174-175 (Frazier) See Author Note The Anasazi Buildings of Chaco Canyon: Largest “Apartments” in the World.

By 900 there were hints of hierarchy [in the Hohokam] not within but between towns, with the largest occupying positions of control at the heads of canal systems—positions of power. (Lekson)

We propose that these southerners [from Mexico, mainly the Toltecs]…entered the San Juan basin around A.D. 900 and found a suspicious but pliant population whom they terrorized into reproducing the theocratic lifestyle they had previously known in Mesoamerica. This involved heavy payments of tribute, constructing the Chaco system of great houses and roads, and providing victims for ceremonial sacrifice. The Mexicans achieved their objectives through the use of warfare, violent example, and terrifying cult ceremonies that included human sacrifice and cannibalism. —Turner/Man Corn pp. 482-483

Atlatl and snares had completely disappeared from Mogollon inventory (Martin, p. 75)

Conch trumpets were first found in ruins of Southwest (Frazier p. 168)

Guadalupe Ruin, easternmost outlier at 54 miles southeast of Chaco, built in this mid- to late-century (Frazier p. 145)

Middle of this decade, the great Maya city-states collapsed [Toltecs?] (Stuart)

The feathered serpent [Xipe Totec] appears in Anasazi rock and kiva art sometime after 900 (Turner p. 466)

Toltec expeditions reached the southern outposts of Mogollon culture (perhaps even Anasazi) (source?)

Toltec invaders entered the San Juan Basin around this time, the inhabitants of which they began to terrorize with social-control cannibalism (Turner)

After this date, relations between the Southwest and Mesoamerica became notably more formal and “patterned” (Lekson, p. 137)

First hints of hierarchy among Hohokam (Lekson p. 232)

La Quemada crashed (Lekson, p. 63)

Before this date, Cotton and Clylcimeris shell armlets were widely imported from the south (Lekson, p. 68)

Cahokia (across the Mississippi from St. Louis) rose rapidly (Lekson, p. 115)

Three Great Houses built in Chaco Canyon by this time (Lekson p. 234)

At this time, only a few elite Chacoan families at most (Lekson p. 236)

Mesa Verde’s Mummy Lake was likely not built to store water. It was built as a…

to 1000

(Pueblo II): skull from this period found in Pueblo Bonito of 45-60-year-old male with dental transfiguration (Turner)

As Chacoan society blossomed in the A.D. 900s and early 1000s, it probably incorporate several once-isolated tribal groups speaking different languages…. As Chacoan society came undone, those ancient linguistic, social, and religious differences would have been rich fodder for ethnic and tribal hatreds acted out in the uplands…[just as] Yugoslavia in the mid-1990s threw off…Tito’s nation and returned to medieval society. —Stuart/Anasazi America p. 143

to 1030

Pueblo II culture

to 1040

Early Pueblo II; Earlly Bonito Phase; Pots: Red Mesa b/w, narrow neckbanded (sand); Small-house aggregation and sharp increase, greathouses appear in numbers in San Juan Basin; Major population rise, beginnings of turquoise industry and crafts, corn ubiquitous in sites, water-control systems appear (Tom Windes)

to 1050

Precipitation at Chaco was unpredictable (Frazier p. 181, from Judge)

to 1100

Road networks built in Schroeder (where? source?)

to 1125

Chaco emerges as first regional center of Chacoan culture (Frazier p. 234, from Lekson)

to 1150

Pueblo II: Chacoan florescence; “Great Houses,” great kivas, roads, etc., in many but not all regions; “unit pueblos” composed of a kiva and small surface masonry room block; corrugated gray and elaborate black-on-white pottery plus decorated red or orange types in some areas (Roberts from Lipe) [Note: Frazier, p. 81, claims Pueblo II is 900 to 1030]

to 940

First Chaco building period: Penasco Blanco, Pueblo Bonito, Una Vida (Frazier p. 174+. From Lekson)

from 200

Mayan culture at its height (Mann p. 304)

to 1000

Roads and colonnades appeared at Chaco Canyon, after La Quemada, whith its elaborate system of causeway roads and colonnades crashed in 900 (Lekson, p. 63)

to 950

Hohokam canals had reached levels of technological and organizational complexity unprecedented in the Southwest and indeed most of North America — well beyond the control of village-level authority (Lekson, p. 81)

to 1150

Hohokam began its long slide down while Chaco pumped itself up; Mimbres, once closely allied to Hohokam, shifted its alliance north to Chaco (Lekson, p. 106)

The biggest, busiest, and best in the long history of the Plateau (including Chaco) (Lekson, p. 111)

Interactions at a distance were impressive: Tula in central Mexico and Chichen Itza more than 1,000 kilometers away replicated in remarkable detail each other’s major monuments (Lekson p. 234)

to 1125

Dubbed the Pax Chaco, a remarkable era of peace blessed the countryside (Lekson, p. 129)

to 1200

Chaco leaders kept the peace, promoted general welfare, enhanced its own glory, and got things done (Lekson p. 235) — and also used social-control cannibalism according to Turner

From 900 to 1200 AD Chaco kept the peace, promoted the general welfare and got things done.

Many things came to Chaco and stayed there, in the service of the kings. Maize moved into and through the canyon, from places that had plenty to places that had none. Consequently, violence and raiding almost ceased. Its success, from 900 to 1000, allowed Chaco’s leaders to expand their horizons. Its influence soon reached far beyond its original domain…. Local leaders almost everywhere on the Plateau joined with or deferred to Chaco…. From 900 to 1200, Chaco kept the peace, promoted the general welfare, enhanced its own glory, and got things done. —Lekson p. 235

One day in 1993, [physical anthropologist Christy G.] Turner and David Wilcox plotted the three dozen cannibalism sites on a large map. “Suddenly,” Turner recalled, “we had a kind of ‘Eureka!’ Nearly every site lay close to a Chaco outlier. And the dates were right—between 900 and 1200. —Roberts/Old Ones, pp. 159-160

880

to 900

Center of Anasazi population was around upper San Juan and southeastern Utah (Lekson, p. 99)

875

to 925

Late Pueblo I to Early Pueblo II; Early Bonito Phase; Pots: Kiatuthlanna @ Red Mesa b/w, Lino Gray & Kana’a Neckbanded; Above-ground slab-house sites, small to moderate in size; Shift from dry to wet period (Tom Windes)

860

There were at least twenty major Pueblo I village sites with an average of 123 above-ground rooms and fifteen or more pit structures (Lekson, p. 95)

At least one third to one half of the known population in the Anasazi world was in the Northern San Juan, a relatively small corner of the Anasazi region (Lekson, p. 98)

856

Nomads known as Chichimecs from Aztlán migrated into the northern end of the Valley of Mexico and founded the capital of the Toltec empire, Tula, 54 miles northwest of Mexico City (Waters, p. 117)

850

Earliest room construction at Pueblo Bonito this decade, not 900s as originally thought (Frazier p. 229, from Windes)

Hohokam intervillage squabbles reached levels of warfare (Lekson p. 233)

to 1000

At least 10,000 farmsteads were established and agriculture reached its widest geographical limits, never to be reached again in prehistoric times (Stuart)

to 864

Longest, wettest period during the 800s (Frazier p. 231)

to 900

Chaco Great Houses began, reaching critical mass around 1000 (Lekson, p. 123)

to 1150

Pueblo Bonito built (Lekson p. 234)

840

to 860

Late Basketmaker, Pueblo I, and early Pueblo II cultures coexisted (Stuart)

to 880

Center of Anasazi population was around Montezuma Valley/Great Sage Plains/Dolores (Lekson, p. 99)

830

to 840

Pueblo II period had begun with the first construction of small blocks of masonry surface rooms on the margins of open valleys (Stuart)

828

to 1126

Pueblo Bonito…was built by the Ancestral Puebloans, who occupied the structure between AD 828 and 1126. (Wikipedia, “Pueblo Bonito”)

825

to 850

Mimbres Three Circle Phase, when lots of really big sites popped up — this means canals really kicked in about this time (Lekson, p. 94)

810

to 860

Center of Anasazi population was around Mesa Verde, Mancos (Lekson, p. 98)

800

Community houses emerged as people became more agrarian (Stuart)

Cultures near Taos, New Mexico, and the Gallina highlands flanking the west side of the Jemez Caldera turned their backs on the emerging Chacoan world and refused to trade with them (Stuart)

Pueblo Bonito built and occupied from mid-800s to 1300s (NPS.gov)

Pueblo Bonito founded sometime in this century (Stuart)

Pueblo I structures began having enclosed ramadas (Mexican influence?) (Frazier p. 90)

Una Vida constructed in mid 800s and inhabited until mid-1100s (NPS.gov)

Una Vida constructed shortly after this date (Stuart)

By this time, the Plateau was lurching toward war — not organized armies, but farily widespread and constant killing, driving people into large villages (Lekson, p. 100)

Metallurgy reached West Mexico from the Pacific coast (Lekson, p. 114)

Great Houses reappeared on the Plateau — not among the Uto-Aztecan kin in the west, but among the native peoples of the eastern Plateau (Lekson p. 232)

to 1000

[D]uring this protracted period of

Toltec cultural strife, between roughly A.D.

800 and

1000, waves of diverse Mexican traits were carried into the American Southwest by cultists, priests, warriors, pilgrims, traders, miners, farmers, and others fleeing or displaced by the widespread unrest and civil war in central Mexico. —

Turner/Man Corn p. 463

to 875

Pueblo I; White Mound Phase; Pots: Whitemound b/w, Lino Gray; Classic above-ground slab row house sites, small to moderate size, first greathouses appear; Major increase in storage facilities (Tom Windes)

to 900

In Chaco Canyon itself, game was already so scarce that it could not provide even 10% of the daily diet; dried meat had to be imported; the Pueblo I pithouses in the Navajo Lake District to the north had become palisaded strongholds and refused to trade with Chaco (Stuart)

to 1100

Aztatlan “horizon,” a series of city centers along 800 kilometers of the West Coast of Mexico linked by long-distance trade to Mesoamerica (Lekson, p. 114)

780

Small Pueblo I settlement across canyon from Una Vida begun: site 627 (Stuart)

770

to 830

Center of Anasazi population was in southeastern Utah (Lekson, p. 98)

750

to 900

Pueblo I: Large villages in some areas; unit pueblos of “proto-kiva,” plus surface room block of jacal or crude masonry; great kivas; plain and neck-banded gray pottery with low frequencies of black-on-white and decorated red ware (Roberts from Lipe)

750

Glycimeris shell armlets became a staple of Hohokam sites (Lekson, p. 59)

Most of the Mogollon region before this time were essentially upland Hohokam (Lekson, p. 64)

By this year, Teotihuacan was gone, removed to myth (Lekson, p. 79)

to 810

Blue Mesa-Ridges Basin, with limited occupation into the 830s (Lekson, p. 97)

Center of Anasazi population was around Durango (Lekson, p. 98)

700

People became Hohokam. Perhaps the most conspicuous and widespread markers of Hohokam were armlets of Glycimeris shell. Bivalve shells from the Gulf of California were carefully shaped into armlets and sometimes carved with symbols—birds carrying snakes, desert toads, and the like. Shell bracelets or armlets became a badge or marker of Hohokam; they had once been rarities, but after 700 they were ubiquitous. Someone in every sizable settlement had armlets prominently displayed on an upper arm. (Lekson)

Intervillage squabbles escalated after 700, occasionally reaching levels approaching warfare by 850. Increasing violence also called for leaders, military or diplomatic. (Lekson p. 233)

Reed cigarettes appeared in Mogollon culture (Martin p. 99)

Cotton became economically important to Hohokam (Lekson, p. 59)

Hohokam defined by ball courts, red-on-buff pottery, stone pallets, complex cremation burial ritual; crashed by 1150 (Lekson, p. 80)

By this time, dozens of sizable pit house village crowded the low terraces where creeks and rives left the mountains and flowed into the Chihuahuan Desert of southwestern New Mexico (Mimbres Mogollon) (Lekson, p. 89)

Mimbres heated up when red-on-brown pottery showed up and riverside village became established and lasted as long as three centuries (Lekson, p. 94)

Intervillage squabbles escalated among Hohokam after this time, approaching levels of warfare by 850 (Lekson p. 233)

to 800

Early Pueblo I; White Mound Phase; Pots: Whitemound b/w, Lino Gray; Deep pithouses that are dispersed; sparse storage facilities (Tom Windes)

to 900

The 934 known Basketmaker sites from this period increased to 1,174 Pueblo I sites by the end of this period (Stuart)

to 1000

Hohokam villages consisted of central plaza surrounded by single-room house clustered in threes or fours around courtyard (Lekson, p. 23)

Evidence of the introduction of cotton fiber to Anasazi land via trade routes through Mesoamerica. With the cotton fiber comes the technologically advanced back strap loom and the vertical frame loom. (Chronology of Textiles and Fiber Art in New Mexico) See Author Note: Anasazi Footwear: Shoe-Socks and Sandals.

to 800s

A tight package of cultural practices came together that define Hohokam (Lekson, p. 58)

Hohokam figurines all but disappeared, replaced by ritual mounds (Lekson, p. 62)

Chaco Great Houses originated in the northern San Juan region (Lekson, p. 123)

to 950

Hohokam exploded outward, then shrank back in on Phoenix (Lekson, p. 69)

Perhaps the most dynamic in the history of the Southwest (Lekson, p. 78)

to 900

Most, and all of the largest, ball courts were built (as a technique for political decision-making that is not clear to science, art, and industry) (Lekson, p. 86)

to 1130

The tenfold Anasazi population growth could not have happened through increased birthrate alone. (Wikipedia)

to 1300

Six rooms and a kiva basic form of Anasazi village

650

Teotihuacan culture in Mexico looted and violently destroyed (by whom?)

Toltec culture began to develop from the ashes of the Teotihuacan culture in Central Mexico

to 750

Grand Gulch on Cedar Mesa in Utah inhabited again, then abandoned again (Roberts p. 131)

La Quemada hit is stride, ending around 900 (Lekson, p. 63)

600

First in a long line of black-on-white Anasazi pottery type appeared (Lekson, p. 57)

By this date, Plateau potters quit digging clay in creek bottoms and began mining pottery clays from geological strata, grinding and tempering them, and firing them a good gray color (Lekson, p. 57)

Teotihuacan collapsed with great violence (Lekson, p. 79)

to 700

Late Basketmaker III; La Plata Phase; Pots: La Plata b/w, Lino & Obelisk Grays; Shallow pithouses that are dispersed; Moderate storage facilities (surface cists) (Tom Windes)

Pit houses became uniform in design (Stuart)

to 750

Burial ideas changed, from one of taboo places away from homes, to burial in abandoned pit houses and nearby kitchen middens — another evidence of shift from hunter-gatherer to farmers (Stuart)

to 800

Road networks built in La Quemada, Mexico

585

Radiocarbon date of one Basketmaker site in Chaco Canyon (Frazier p. 90)

550

Basketmaker III really heated up (Lekson, p. 65)

After the fall of Teotihuacan, Southwest Big House leaders emulated the southern kings of Mesoamerica.

The fall of Teotihuacán [thirty miles northeast of modern-day Mexico City] (about 550) sent tsunamis of political power outward, rulers looking for places to rule. In the following decades, displaced, dispersing elites transformed cities and towns throughout Mesoamerica.…Petty chiefs and Big House leaders [of the Four Corners]…were tempted to emulate southern kings. —Lekson p. 231

Teotihuacan collapsed with great violence (Lekson, p. 79 & 231)

to 600

Teotihuacan crashed (Lekson, p. 62)

to 950

Late Pithouse Period for, particularly, the Mimbred Mogollon (Lekson, p. 89)

500

After this date, “the severe, magnificent tapering-bodied anthropomorphs of Basketmaker II grow smaller, ‘cuter,’ squatter, and more triangular.” (Roberts p. 179)

Some years before this, Cave 7 in Whiskers Draw [where is this? Near Blanding, Utah, I think] more than ninety men, women, and children were killed, perhaps ritually executed, many were scalped and tortured before death (Roberts p. 186, from Turner)

Cotton arrived in Arizona Hohokam region (Lekson, p. 59)

La Quemada began (Lekson, p. 63)

Teotihuacan was the principal fact of central Mexico and all points north (Lekson, p. 79)

to 600

Basketmaker III; La Plata Phase; Pots: La Plata b/w, Lino & Obelisk Grays; Shallow pithouses, two aggregated great communities with great kivas appear; Moderate storage facilities (surface cists) (Tom Windes)

to 750

Basketmaker III: Habitation is deep pithouse plus surface storage pits, cists, or rooms; plain gray pottery, small frequencies of black-on-white pottery; bow and arrow replaces atlatl; beans added to cultigens (Roberts from Lipe)

to 700

Hohokam socially differentiated with oversized or special architecture fronting plazas at Snaketown and Valencia Vieja, with beginnings of mortuary practices that indicate ritual and political leaders (Lekson, p. 58, citing Wallace and Lindeman)

450

A slipped redware was added to Hohokam and Mogollon assemblages but not to those of the Anasazi, who instead began to paint images on their pottery 56)

to 500

First beans and first pottery coincide (Roberts p. 185)

to 525

Hohokam populations aggregated (Lekson, p. 58)

400

From this year onward, corn cob size increased (Stuart)

A horizon of small pit houses sites, all sharing a common brownware, extended from southern New Mexico and Southern Arizona (and probably northern Sonora and Chihuahua) north to the San Juan River drainage (Lekson, p. 56)

Canal technology of Tucson and Land Between spread into the Phoenix Basin (Lekson, p. 59)

Late this century, new, more productive corn arrived in Arizona Hohokam area (Lekson, p. 59)

to 500

Late Basketmaker II; Brownware Phase; Pots: Obelisk Gray & brownware (Tom Windes)

to 750

Late Basketmaker period (Stuart)

to 500

Substrate of agricultural pit houses using brownware pottery (Lekson, p. 47)

to 700

The archaeological patterns we call Anasazi, Hohokam, and Mogollon emerged (Lekson, p. 49)

Teuchitlan cities, with their round, terraced, wedding-cake pyramids, flourished (Lekson, p. 63)

to 500

Teotihuacan peaked (Lekson, p. 62)

300

By this time the Teotihuacan culture dominated much of central Mexico

to 400

Pottery came to Four Corners area (Stuart)

200

Dental transfiguration began in Northern Mexico (Nuevo León)

to 400

Grand Gulch on Cedar Mesa in Utah first inhabited, then abandoned (Roberts p. 131)

to 900

Mayan culture at its height (Mann p. 304)

to 500

Best dates for brownware pottery in Four Corners Plateau (Lekson, p. 46)

to 550

Early Mimbre and other Mogollon areas had a notable predilection for high places: buttes, mesas, hilltops — notably unlike Hohokam, who lived down by the river (Lekson, p. 64)

to 950

Teotihuacan dominated Mesoamerica, sending emissaries and enclaves to the heart of the Maya region and to the north (Lekson p. 228)

150

Settlements in pre-Hohokam culture changed from intermittent to permanent (Lekson, p. 58)

to 200

Best dates for brownware pottery in Four Corners deserts (Lekson, p. 46)

100

Macaws found in ruins of Hohokam culture (Frazier p. 168)

The more livable portions of the Chacoan plateau were occupied, beginning the political tensions of over-crowding (Lekson, p. 128)

50

to 500

Basketmaker II (late): Habitation is shallow pithouse plus storage pits or cists; no pottery; atlatl and dart; corn and squash but no beans (Roberts from Lipe)

1

Incense burners found in Hohokam ruins at least this far back (Frazier p. 168)

Water tables rose in SW, meaning more constantly flowing streams, springs, more ponds (Stuart)

Teotihuacan began, peaked 400-500, crashed 550-600 (Lekson, p. 62)

to 300

Bow and arrow appeared, imported from northern Great Plains (Stuart)

to 400

Early Basketmaker period (Stuart)

-100

States had convincingly risen in Mesoamerica (Lekson, p. 63)

to 400

Hopewell occupied (Lekson, p. 47)

-161

“The famous Cato, a dour and hard-fisted old farmer, who treated his own slaves as they aged with notorious callousness, was then censor, an office with wide powers over morals and manners. Though himself an able speaker, he was hostile to those who taught the art. In 161 B.C., teachers of rhetoric were expelled from Rome.” (Stone, p. 42) This is an example of how the rich and powerful of a society that ultimately collapsed quashes free speech and the education of common citizens.

-200

The centralized and stratified Teotihuacan culture began developing in the Valley of Mexico

-300

Cooking, storing, and serving pottery first appears in Mogollon culture (Martin p. 83)

-500

500 BC – Around this date, waves of Uto-Aztecan speakers moved onto the western Four Corners Anasazi plateau (Lekson, p. 46)

Beans appeared in the American Southwest (Stuart)