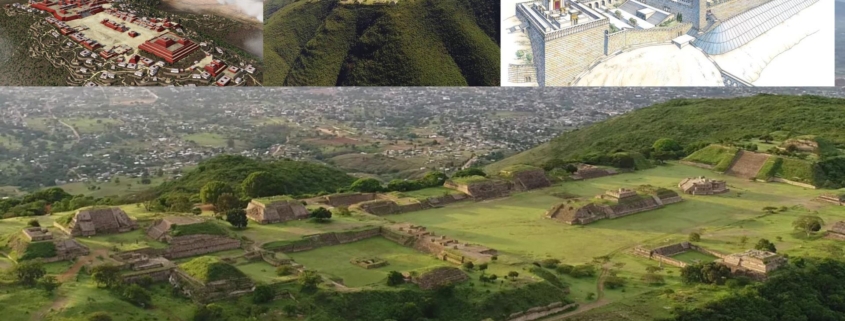

Monte Alban Oaxaca as the City & Land of Nephi

Outline of Correlations of Monte Alban with City of Nephi

- Site timeline matches perfectly. (City founded around 600 BC. Massive improvements 200 BC)

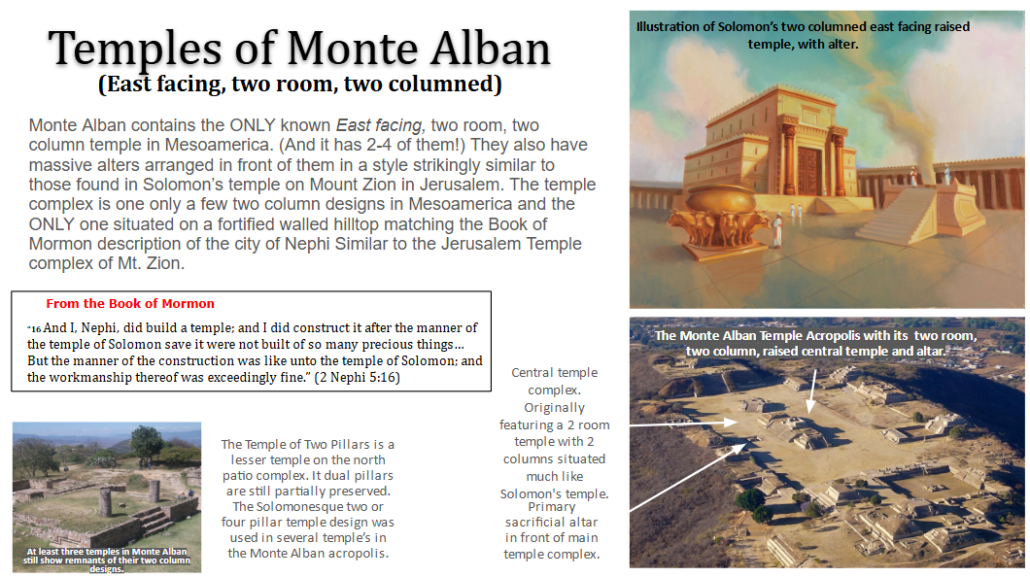

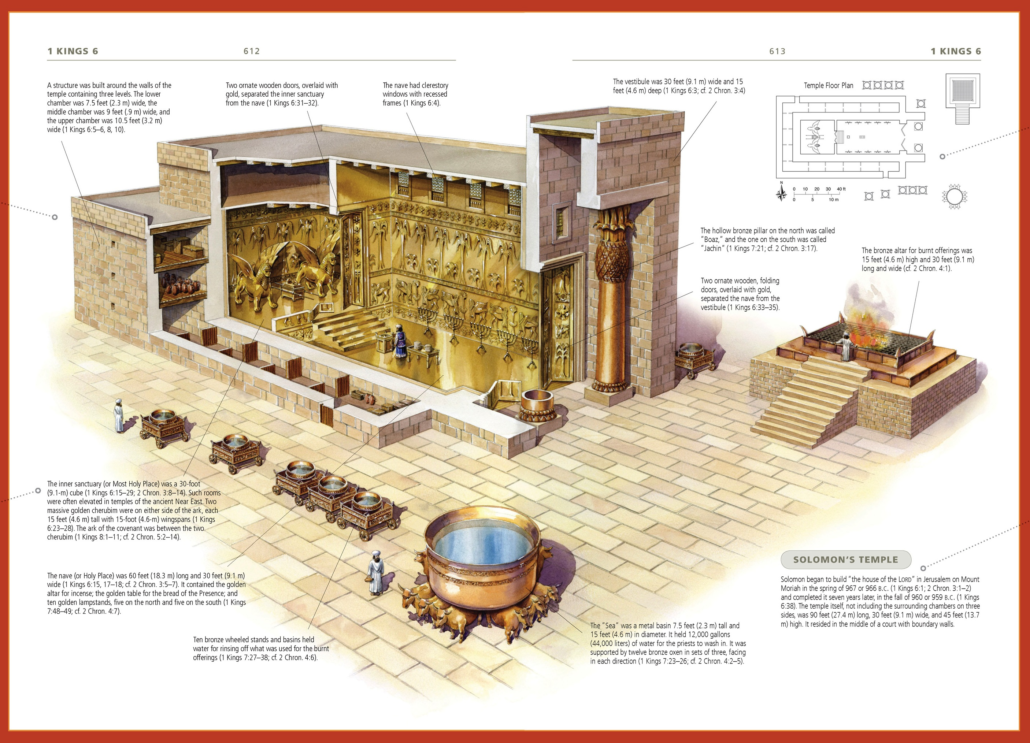

- SEVERAL of the ONLY known east facing, two-room, two-column (Solomon-like) temples in the ancient Americas. With ground penetrating Radar showing that the original 2 room, 2 column temple was shaped even more like Soloman’s than the 4 or 5 still existing at the site today. (and was likely built at the same time as the site at ~550 BC). In front of the building were alters (like the one still extant), and water basins/cisterns as well as evidence of incense burning, animal sacrifice.

- Its temple alignments facing East to mark spring passover, and Observatory facing NE or Capella to mark pentecost and even a solar tube to mark the Zenith.

- Even the name ‘white hill’ and tomb/pyramid layout match amazingly with Jerusalem’s famous white limestone motif.

- Preceded by a ‘priest-cult’ with ‘men’s houses’ which have first 2 room temples in MA. (sound awfully similar to Israel).

- Rock reliefs of ‘genital mutilation’ which are strikingly similar to Egyptian circumcision motifs.

- The dry, mediterranean-like climate matches well with Israel, so old-world crops could grow.

- Evidence of social stratification & polygamy amidst otherwise monogamous culture.

- A later ‘split’ in the valley between two dominate warring factions. Who divided the valley between them.

- A later royal palace (El Palenque Palace) built around 200 BC that could match well with Lemhi reinhabiting the land.

- 10-the New LDS temple was built directly east, aligned with the ancient temple and altar.

Archaeologists from the University of Oklahoma recently pinpointed the location of a buried building about 30 centimeters beneath the surface of the Main Plaza at Monte Albán — one of the first cities to develop in all of pre-Hispanic Mexico. The team used three geophysical prospection techniques — ground-penetrating radar, electrical resistance and gradiometry — to locate the square structure, which is estimated at 18 meters on a side and with stone walls more than a meter thick. OU researchers are the first to employ gradiometry and electrical resistivity at the site.

The hidden building appears to resemble stone temples of a similar size from Monte Alban that were excavated by Mexican archaeologists in the 1930s. Evidence from these temples indicate they were used for religious practices, including burning incense, making offerings and ritual bloodletting, said Marc Levine, associate curator of archaeology at the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History and associate professor in the Department of Anthropology, College of Arts and Sciences. Researchers continue to analyze data from the new building to see if they can detect other features, like stairways, columns, tunnels or associated offerings. (reference, ref2)

By roughly 1000 BC in conventional radiocarbon years (calibrated 1800 BC), it appears that some of Oaxaca’s larger Formative villages were run by elite individuals who had differential access to iron ore mirrors, mother-of-pearl, Spondylus shell, jadeite ornaments, and exotic pottery from other regions. These individuals were also treated differently at the time of their burial, even when they died as children.

Ignacio Bernal’s field notes led the UMMAA project to sites such as San José Mogote, Huitzo, Fábrica San José, and Tierras Largas in the northern Valley of Oaxaca, and Abasolo and Tomaltepec in the eastern valley. These excavations were funded by the National Science Foundation.

Of all these sites, San José Mogote turned out to have the longest sequence of Formative cultures. It also grew to be the largest village in the valley prior to the founding of Monte Albán, Oaxaca’s first city. Three other villages were excavated by graduate students for their PhD theses: Tierras Largas by Marcus Winter, Fábrica San José by Robert Drennan, and Tomaltepec by Michael Whalen.

UMMAA excavated at San José Mogote for 15 field seasons (1966-1980). The site yielded more than 30 residences and 30 public buildings. In publishing their reports on the site, Flannery and Marcus decided to deviate from the traditional format of site reports. The latter were typically composed of chapters on pottery, chipped stone, ground stone, animal bones, and so on. This format made it tedious to reconstruct all the materials found in a given residence.

Flannery and Marcus decided that the residence should be the unit of analysis. In their first volume on San José Mogote, therefore, they listed the complete contents of every Formative house. This made it possible to identify neighborhoods at San José Mogote and to show which households were involved in chert biface manufacture, press molding of pottery, shell working, or the polishing of iron-ore mirrors.

In their second volume on San José Mogote, Flannery and Marcus presented the layout and contents of every public building recovered. This approach made it possible to reconstruct the evolution of Zapotec ritual and religion.

San José Mogote appears to have been founded during the Espiridión phase, a period for which no 14C dates are available. The undecorated pottery of this phase appeared in a limited number of shapes, all of which resemble the gourd vessels used during the Archaic.

By the Tierras Largas phase (calibrated 1800-1300 BC), San José Mogote was a village of wattle-and-daub houses covering perhaps 7 hectares. It was defended (at least on its west side) by a palisade of pine posts. The dominant ritual buildings were small (4 x 6 m) men’s houses, oriented 8˚ N of true east. They differed from Tierras Largas residences not only by their orientation but also by multiple layers of lime plaster. Among the burials of this phase were middle-aged men (presumably community leaders) who were buried in a seated, tightly flexed position. This differed from the fully-extended position of most men’s and women’s burials; however, no luxury goods were found even with the seated burials.

The San José phase (calibrated 1300-950 BC) was a period of spectacular growth. San José Mogote now consisted of a nucleated main village (20 hectares), surrounded by outlying barrios which increased its size to 60-70 hectares. Within 8 km of this large village were 12-14 smaller villages and hamlets which appeared to be satellite communities. So great was this growth that it must have included immigration as well as population increase.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that San José Mogote had now become a chiefly center. Its main village center now included pyramidal temple platforms, which gradually replaced men’s houses over time. Sumptuary goods included jadeite, iron ore mirrors, mother-of-pearl, and Spondylus shell. The figurines of the period depicted people of rank and people of lower status. Craft specialization differed by residential ward, as did iconographic motifs on the pottery. Some families at San José Mogote received gifts of ceramics from the Basin of Mexico/Morelos, the Gulf Coast, and the Pacific Coast. Iron ore mirrors polished at San José Mogote were sent to elite families in the Olmec area and the Valley of Morelos.

The western limits of San José Mogote produced the partial remains of a similar cemetery, most of which had been destroyed by Colonial and recent adobe makers. Finally, the village of Abasolo yielded the burials of infants or children too young to have been initiated. Some were accompanied by elegant vessels with Sky or Lightning motifs, suggesting that the right to such vessels was inherited rather than achieved.

Several San José phase villages featured cemeteries. At Tomaltepec, Michael Whalen discovered a cemetery of roughly 80 adults, including a number of presumed husband-wife pairs. Six men stood out as different — buried in a seated position, so tightly flexed as likely to have been bundled. Although constituting only 12.7% of the cemetery, these six men were accompanied by 88% of the jadeite beads, 66% of the stone slab grave coverings, and 50% of the pottery vessels carved with “Sky” or “Lightning” motifs. Many also had secondary skeletal remains added to their graves, raising the possibility that elite men might have had multiple wives, some of whom preceded them in death.

During the subsequent Guadalupe phase (for which we have only a few radiocarbon dates), other chiefly centers arose to challenge San José Mogote’s political influence. Huitzo (to the north) and San Martín Tilcajete (to the south) may have interfered with San José Mogote’s access to some of its favorite iron ore sources, effectively ending the production of iron ore mirrors. The Guadalupe phase seems to have been a period of retrenchment, during which San José Mogote lost population. Notwithstanding this period of “chiefly cycling,” the leaders of San José Mogote built temple platforms of plano-convex adobe bricks, facing onto modest ceremonial plazas. Elite women from San José Mogote may have been sent to marry leaders at satellite communities such as Fábrica San José. There Drennan found elite women, with the same cranial deformation seen at San José Mogote, buried with sumptuary goods.

During the Rosario phase (calibrated 900-600 BC) San José Mogote returned to prominence, covering 60-70 hectares. A natural hill in the main village became an acropolis for temples on stone masonry platforms of travertine and limestone. At some point in the Rosario phase, public building orientation changed from 8˚ N of East to true North-South. At almost every stage of construction, sacrificed individuals were added to the fill.

At this time period, the Valley of Oaxaca was controlled by three rival chiefly societies. The northern valley was controlled by San José Mogote, the eastern valley by Yegüih, and the southern valley by San Martín Tilcajete. So hostile to each other were these rival societies that a virtually unoccupied buffer zone developed in the central valley.

Late in the Rosario phase, San José Mogote was attacked and its main temple burned. San José Mogote responded by building a new temple nearby and carving a stone monument that depicted an enemy leader whose heart they had removed. The victim’s hieroglyphic name was added, and the stone was placed horizontally in a corridor where the slain enemy’s image could be trod upon.

The Rosario phase ended when 2000 people from San José Mogote and its satellites left their vulnerable valley floor locations and moved to a 400 meter-tall mountain in the buffer zone. From this new, more easily fortified summit they set about subduing their rivals.

RE-WRITE THE ABOVE & REPLACE PICS. from Origins of Social Inequality, Flannery & Marcus, 2021.

.

Metallurgy in Oaxaca

Write this section. Late in date, but likely the richest collection of Metalurgy in Mesoamerica. I’ve read 80% of all metal artifacts come from Mixtec lands. Probably because the rest of Mesoamerica was thoroughly looted by Spanish and everyone since. Tomb 7 (from circa 1000 AD) is the biggest cache of all, and was produced locally in Oaxaca. Probably just a taste of what exists and I suspect they will one day find a great cache from 500 BC.

Get more info on these… Pretty sure they are from tomb 7.

.

In addition to the weakening of San José Mogote’s influence

on other villages’ pottery styles, other lines of evidence suggest

that San José Mogote had lost some of its political clout. During

the Guadalupe phase, for example, San José Mogote seems to

have lost access to two of its principal iron ore sources: Loma

de la Cañada Totomosle, north of Huitzo, and Loma los Sabinos,

not far from the emerging chiefly center of San Martín Tilcajete

(Flannery and Marcus 2005:87). The Guadalupe phase would

thus appear to represent a downturn in San José Mogote’s cycles

of waxing and waning political power.

Vessel 3 (Fig. 6.5) does not belong to any of our usual Oaxaca

Formative pottery types, and is likely a foreign import… We showed this bottle to David C. Grove and he suspects

that it may be a Valley of Morelos pottery type, Madera Coarse

(Brown variety)

We wish that Burial 65 had included enough skeletal elements

to allow its sex to be determined. In our experience, individuals

in Formative Oaxaca who were buried with a “female ancestor”

figurine tended to be women, and we would like to have been able

to confirm this by skeletal criteria. We are also curious about the

possible vessel from Morelos. The Middle Formative was a time

when high-status women were exchanged as brides (Marcus and

Flannery 1996:114–115, 134–135) and we would like to know

whether such exchanges linked Morelos and Oaxaca

What does it mean when a settlement is left abandoned for

decades—even centuries—only to have a small group of people

return and build an altar on its highest promontory? This kind of

event happened so often in ancient Oaxaca that it can be considered a recurring process.

We suspect that Structures 23 and 24 are examples of a phenomenon that has become fashionable to call “social memory.”

We are not particularly fond of this term, since it too often serves

as a shiny new package for what anthropologists previously called

“tradition.” Nor do we necessarily believe that the Zapotec of

400 b.c. remembered everything they had done at 700–500 b.c.

By then, it is more likely that they had begun to revise their own

history to accomplish new goals.

We do know, however, that many Mesoamerican societies

memorialized past events in terms of legendary homelands and

heroes. The Zapotec, in particular, referred to dynastic founders or “founder couples

Add sections from this Book showing the connection of both pottery and iron mirrors between Morelos and Oaxaca.

https://archive.org/details/sanpablonexpaear0000grov/mode/2up

Excavations at San José Mogote 2: The Cognitive Archaeology:

God placers of Oaxaca: https://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/2365?lang=en

Check out these pics of some of the less known sites in Oaxaca Valley (I need to visit these & get pics):

https://sailingstonetravel.com/ex-convent-of-cuilapam-zaachila/

https://sailingstonetravel.com/oaxacas-overlooked-zapotec-sites-yagul-dainzu-atzompa/

I need to make a map of all the impressive sites of Oaxaca, and add pics of each surrounding the map to show how many there are. Include Monte Alban, Mitla, but also Yagul (visited. ballcourt, tombs), Zaachila (tomb & site south), Dainzu, Atzompa, Huijazoo (crazy huge stone lintels of tomb 5)

Add to the article this info:

The name Oaxaca comes from the Nahuatl word “Huaxyacac”, which refers to a tree called a “guaje” (Leucaena

Important because Oaxtepec (where the famous aztec gardens are) comes from the same native word! It means “hill or mount of huajes”, EXACTLY THE SAME AS MONTE ALBAN/OAXACA. Interestingly, Cholula is next to a hill called ‘Cerro Zapotecas’, once again pointing to a connection to Oaxaca & the Zapotec of Monte Alban, as well as a nearby neighborhood & old pond called Zerezotla, which especially if ancient people pronounced the second ‘z’ like an ‘h’ sounds somewhat similar to Zarahemla. Also, this plant is a hallucinagenic! (psychotomimetic plant)

Google… “is Leucaena leucocephala a hallucinaginic?”

Talk a bit, and add pictures of Aztec Gardens. Both Oaxatepec and NEZAHUALCÓYOTL

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leucaena

https://oaxacaculture.com/2014/07/oaxacas-monte-alban-archeological-site-key-to-zapotec-civilization/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oaxtepec

Connections With the Land of Zarahemla (Puebla/Morelos)

McCafferty, 1996, notes that the giant head on display near the base of the Pyramid of Cholula matches closely with those found at San Juan Diuxi in the Mixteca Alta, as well as the giant anthropomorphic frog head at Yagul, Oaxaca (pic). which is also relevant as early maps depict the pyramid at Cholula with a frog on top of a hill (see Chistlieb, 2015).

These motifs both likely correlate with the Egyptian goddess Heqet. A common fertility motif from the Early Dynastic Period. [add illustration of Haqet and the two heads]

David Grove’s book (Grove, 1974) on the excavations of Nexpa, Morelos cites numerous examples of goods which suggest a trade network between Morelos/The Mexican Highland (our Land of Zarahemla) and the Valley of Oaxaca (our Land of Nephi). What’s most interesting about this evidence is how early and continuous the trade was. The conclusions it leads us to in the Book of Mormon narrative make us wonder if Mosiah knew to flee to the people of Zarahemla (probably because they had trade relations), and some span of time later Zeniff knew of the “goodness” of the Lamanites of the Land of Nephi (probably because they traded with them in addition to fighting with them). Then why did Lemhi loose track of the location of the land of Zarahemla? Is it because passage on the known roads between the two lands was blocked by the expanding Lamanite influence in the Mixtec Alta forced them to take another more confusing route?

(Grove, David C. San Pablo, Nexpa, and the early formative archaeology of Morelos, Mexico. 1974. Nashville, Tenn. : Vanderbilt University)

“Extensive evidence exists for a Classic-era Oaxacan-Zapotec presencein and about Cholollan and more generally within the Basin of Mexico. Such a presence has been documented by way of the quantities of Oaxacan graywares present on a number of such sites (Crespo Oviedo and Guadalupe Mastache 1981; Diaz 1981), Zapotec-type full cruciform and small niche tombs and related architectural features (Hirth and Swezey 1976), Monte Alban-type ceremonial and mortuary offerings (Millon 1967), and Zapotec iconographic and calendrical elements in circum-Basin contexts (Lombardo de Ruiz, et aI., 1986). Concommitantly, while the presence of a Oaxacan enclave at Teotihuacan, replete with cruciform tombs and mortuary offerings, has long been acknowledged (Millon 1967; Paddock 1983; Rattray 1987), only recently have scholars begun to similarly acknowledge such a presence in other Basin and circum-Basin contexts (Crespo Oviedo and Guadalupe Mastache 1981; Hirth and Swezey 1976). Taken together, such recent finds as those described for Chingu, Manzanilla, Los Teteles, Cholollan, and most recently, Xochicalco, present a strong case for a Zapotec pre3ence in the central highlands (Millon 1988; Crespo Oviedo and Guadalupe Mastache 1981)

“For the intermediate region of Puebla, Peterson (1987:110) cites evidence for the presence of Monte Alban III style ceramics for the Classic period occupation of Cholollan. Peterson (1987:110) notes personal communication with Merlo (1977) and Charles Caskey (1983), respectively, in presenting evidence of (a) “Monte Alban III style urns or fragments” discovered on the northern outskirts of Cholula, Puebla, in an area of “high sherd density”; and (b) “Zapotec style materials” unearthed during the excavations associated with the Hotel Villa Arqueologica in Cholula. In addition, “Zapotec style materials” have been unearthed on the northern perimeter of the city of Puebla, from tombs at the site of Los Teteles de Ocotitla (Reliford 1983; Hirth and Swezey 1976).”

From: Conquest polities of the Mesoamerican Epiclassic: Circum-Basin regionalism, A.D. 550-850. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185780

The Zapotec enclave at Teotihuacan give ample evidence to Zapotec imports in the Mexican Highland around the time of Christ, but later examples might point us toward where Nephite migrants might have created earlier communities. A few of the best examples are Toluca, Los Tetales & El Tesoro near Tula. “We describe tombs and ceramic collections in Zapotec style excavated in central Mexico, outside Oaxaca. The most notable are 13 ceramic vessels and objects from the Xoo complex (a.d. 500–800) excavated by José García Payón in Calixtlahuaca (near the city of Toluca), and three Zapotec-style tombs excavated in Los Teteles (near the city of Puebla). We also mention Zapotec remains excavated near Tula, Hidalgo, and tombs in other parts of central Mexico. We briefly explore the implications of these data for our understanding of central Mexico after the fall of Teotihuacan.” (Smith & Lind, 2006 – This paper has a map and description of MANY Zarahemla area cities with Oaxaca ceramics and tombs!)

Important ones from the map above are the Tehuacan/Teteles sites because they might be Jerson. And the Toluca one, because those sites have cruciform alters AND apparently oaxaca cruciform tombs. Probably because with Xochicalco, a major nephite/lamanite enclave formed there. (which I felt when I was there)

NOTE: Richards mentions lots of ruins that aren’t anywhere else. He says “It would be impossible to mention all the mounds that are found around the city of Oaxaca, almost every village has ruins of some sort, principally mounds and tombs.” https://dn790008.ca.archive.org/0/items/ruinsofmexico01rickuoft/ruinsofmexico01rickuoft.pdf

Concerning Acatlan, In the same book Richards also gets the impression that “probably the Aztecs fought a great battle here and defeated the Mixtecos, and the warriors, to commemorate the events had these Aztec hieroglyphics put on the rocks as an everlasting memorial”. Which I should add to my book when taking about the forts of the region.