MesoAmerican/Mayan influence on Mississippian Culture

from https://www.facebook.com/notes/suppressed-histories-archives/mound-building-in-north-america-is-old/375806979116303/

Recently, claims of Maya migrations to Georgia have gotten a lot of attention. A long-standing pattern interprets North America as a backwater that absorbed influences from Mesoamerica, repeatedly assumed to be more advanced. in “America’s Lost City,” Andrew Lawler lays out a body of archaeological evidence for major mound complexes in Louisiana and Illinois that predate the Maya and even Olmec ceremonial complexes. (Sorry, link does not give the full article: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/334/6063/1618.summary)

First, the great ceremonial center of Cahokia was even larger than first imagined. They started excavating East St Louis in a big rush before the building of a bridge and road, and found out that Cahokia extended to that area ten km to its east. It was a vast metropolis, home to tens of thousands of people. They traded extensively with faraway places, and settlements closely linked to Cahokia have been found in places like Trempeauleau, Wisconsin. “As recently as the 1950s, a popular scientific theory touted ancient Mayans rather than Native Americans as the mounds’ creators.” But Lawler says scholars are reevaluating things in the light of evidence that the roots of the mound-building cultures “stretch back even earlier than the grand civilizations of Mesoamerica.” Cahokia itself, if it had been found in the Maya country, “would be a top 10 of all Mesoamerican cities,” in the words of John Clark.

It’s well known that the largest mound there equates in footprint to the Great Pyramid, in circumference to the Pyramid of the Sun in Mexico. Scholars have authenticated mound alignments with sunrise at solstices and equinoxes. Archaeologists are excavating another ceremonial settlement 64 km to the south of Cahokia, with its own plaza and mounds. They are finding that people came from all over the Midwest to settle here. There were workshops making ornaments from pipestone, red jasper, copper, and other materials. They’ve also investigated why the city collapsed around 1300, with extensive evidence of floods, droughts, and other changes in weather.

The curved rows of mounds at Poverty Point, circa 1400 bce

The curved rows of mounds at Poverty Point, circa 1400 bce

But Cahokia is fairly well known. The more significant information in this article is the demonstration of the antiquity of mound-building cultures in the Mississippi and Ohio river basins. I’ve posted images here before from Poverty Point, Louisiana, which was another ceremonial complex far older than Cahokia. These northern lands of Louisiana are rich in mounds and ancient villages with radiocarbon dates back to the Middle Archaic period “which ended at about 3000 BCE.” Lawler contextualizes this for us: “That’s nearly 2 millennia before the first cities appeared in Mexico, before the Giza periods, and about the same time that the world’s first major urban centers evolved in ancient Mesopotamia [Iraq]. Most researchers dismissed the dates as erroneous.” Yes, they often do when evidence contradicts their expectations. Archaeologist Joseph Saunders began to study the mounds in northern Louisiana: the six mounds at Hedgepeth, another six at Frenchman’s Bend, along with village remains, and Watson Brake with eleven mounds, and dates going back to 3500 bce. Saunders lays out three major cultural waves of mound-creation. The first emerged in the lower Mississippi valley, 3700-2700 bce. The second, in the same region, centered on Pottery Point, 1600-1000 bce, with a gigantic flying bird mound, 22 m tall and 200m long. It lies atop another set of concentric hemispherical earthworks that covers three hectares, along with other conical and platform mounds. The people here had a vast trade network reaching to the Great Lakes. They made female figurines of clay, carved animals of jasper and other fine stones, and large numbers of bone awls show that they were working leather.

Clay figurines from Poverty Point, Lousiana

Clay figurines from Poverty Point, Lousiana

Even more intriguingly, archaeologists are discovering, “The proportions used at the Louisiana sites closely match those found in Mesoamerica.” They are now considering the possibility that Louisiana may have influenced the Mexican civilization rather than vice versa. The third period of mound construction started in the early centuries CE, in the Ohio river network of the Adena and “Hopewell” cultures, and culminated with Cahokia, Moundville, Alabama, and other medieval American temple complexes.

After the European conquests, many mounds became overgrown and no longer even recognizable as made by humans. “Mostly, the mounds were ignored and then destroyed.” Farmers leveled them, treasure hunters ransacked them, as they did to Spiro Mound in Oklahoma, and cities bulldozed them. The shellmounds in California were similarly destroyed, the burials taken away by the tens of thousands, and still held captive in museums like the Lowie at UC – Berkeley. In Peru, treasure-seekers went so far as to divert streams in the attempt of laying open the adobe pyramids of the Moche. This process of destruction continues today. These historical monuments of immeasurable value are subject to the whims of property owners. The article describes how developers planned to destroy the mounds at Frenchman’s Bend, some of the oldest known, so that they could make a golf course on the site. State and federal law offer no protections for these heritage sites. The archaeologists scramble to talk owners into preserving them, and sometimes even buy up the land to protect the mounds.

Update:

I just ran across a reference to dramtic corroborating evidence from Mexican archaeology. Tom Gidwitz in “Cities upon Cities” in Archaeology magazine, Jul/Aug 2010, writes about how new digs in Huastec country “may reveal links between Huasteca settlements and mound-building cultures in the United States.” He continues: “For decades, archaeologists have theorized that North America’s Late Woodland and Mississippian cultures drew inspiration from the Huastecas, but after their excavations at Tamtoc in the 1990s, Dávila and Zaragoza became convinc…ed that cultural influence, and perhaps actual migration, spread from north to south. They unearthed objects that seemed to come from the American Southeast in about AD 900: a fragment of a sheet of hammered copper, a pointed metal hand tool, a piece of engraved shell, a cache of a dozen whole and 20 fragmented Cahokia projectile points, and pottery that could have come from sites to the north such as Etowah [Georgia] and Moundville [Alabama].”I pulled this quote off of a fragmentary jpg on the net. When i track down the article, I’ll post more about it. In the meantime, here are two engraved shells whose stylistic similarity struck me a decade ago. On the right, from the Mound-temple cultures of the Mississippi basin, and on the left, from the Huastecs of eastern Mexico, the very group now being investigated for northern cultural influences. Check out the hatch-marking especially.

reblogged from http://globalwarming-arclein.blogspot.com/2012/01/mayan-influence-on-mississippian.html

In this case it is taken as a given that the Mississippian cultures are a cultural conglomerate: MESOAMERICA IS ONE OF THOSE CULTURAL CENTERS WHICH GOES INTO THAT CONGLOMERATE. We already KNOW that the temple mounds come out of Mesoamerican pyramids and are something new and different when they come into the mound area. Similarly, there are other features which seem to be part of that same package that came with the idea of those temple mounds. So going around saying “No Mayas here, HaHaHaHaHa!” does not automatically make the person that says it sound smart. The whole reasoning on that score seems to be that the presumption is absurd. The presumption is NOT absurd, it is already a given that something along those lines MUST have occurred. These cultures do not exist eternally as unchanging packages that evolved locally and never had any outside input from cultures further off. THAT is the absurd pretense. There is no assumption that the temple mounds simply involved in situ from burial mounds: there was a radical change in what the mounds meant and what they were made for.

We are talking about the Yucatan Mayas. It is known as an established fact that these Mayas traded as far as Puerto Rico and that there are many of their characteristic ball courts there. The location in question in Georgia is as far from Yucatan as Puerto Rico is, by direct measure on the map.

Now then, as to The Examiner. I do not know what kind of intellectual elitism is going on here but conceptually there is little difference between a “content farm” and the Wikipedia. IN THEORY the Wikipedia should be better checked and independently confirmed. In actual practice, I have found all too many time I have put quite valid information up on Wikipedia only to see it repeatedly torn down by some know-nothing that has their own pet theory to push, and they can quite obviously fly in the face of published authority and even mathematical proofs if only they are persistent enough. The end result is that anybody in the world can put something up on Wikipedia and the information can bear little relationship to the truth of the matter. So I would say don’t go around looking to ANY one authority, ALL authorities have flaws. Read all you can from every source you can, and don’t take anything anybody ever tells you at face value. I loved my mom dearly, but when I became an adult I found that all through my childhood she had been giving me misinformation that was deliberately meant to warp my views. And there was no malice to it, she simply believed very firmly in certain wrong things and she would drum those wrong things into me.

But actually, if something is true it will be true no matter who should say it, and if a matter is false it will be false no matter who says it. The whole basic concept of a “Reliable source” can be misleading, nobody is ever 100% correct. After a while you will come to know what is a good idea or a bad idea from your own perspective. And I am not about to try to tell you what you should think is right or wrong for you, all I can do is make some suggestions about what sounds right or wrong from MY perspective.

The first feature to be noted is that a new ethnic element intrudes into the Mississippi Valley area at the beginning of Mississippian times. They show traits of their cranial anatomy which resemble Mexicans and Mayans more than the Eastern Woodlands tribes and they tend to be somewhat shorter. They also deform their skulls in the same way as the Mayans do. Yes, they are coneheads. At some Mississippian sites it is difficult to find skulls which were NOT deformed in infancy.

The next thing to be noted is that they represent themselves artistically in a manner reminiscent of the Mayans and other South-Mexican cultures, with similar red-pottery figurines:

Now as to the pottery which is allegedly just like Mayan Pottery: That part is true also but it does not begin to tell the whoile story. In fact this is something which has been known for a long time and is one of the key features to understanding the Mississippian cultures. In 1928, Dr. G. C. Valiant published Resemblances in Ceramics of Central and North America, after doing a series of investigations in Mexico for the American Museum of Natural History. He had discovered a series of ceramic traits which he called the “Q Complex” for convenience’s sake. He introduced his subject with these words:

I shall endeavour to call attention to several curious parallels found mainly in the ceramics of Central America and the Southwestern and Southeastern United States That seem to indicate some sort of a relationship, even taking into account the barrier of five hundred kilometers of archaeologically unknown territory…While the Antillean influence on the far southeastern United States is attributable to direct contact[and known settlements over much of Florida-DD]…The traits existing in the pottery of the Western drainage of the Mississippi and to a lesser degree in Tennessee [and adjoining Georgia and Alabama-DD], however, are of a character that indicates a stronger source of infection than a symbolism brought in perhaps by exiles from another land. In short, in the Western Mississippi valley, there exists apparently some sort of action by one culture upon another. These ceramic traits which are quite foreign to the run of the pottery of the eastern states include:

1. Tripod support of vessels.

2.Funnel-necked jars.

3.Double-bodied jars.

4.Rarely, the shoe form of vessel.

5.the high and low form of annular base for vessels.

6. Spout handles

7.the composite silhouette form of bowl.

8. Vessels modeled in the effigy of animals or humans.

9. Vessels with spouts, in plain and in effigy

10. Vessels with the head or features attached

And ended with the conclusions that:

It does not seem possible to explain away such parallels as these by independent invention of styles since the basis of the ceramic development of the Eastern United States does not seem to contain the germs for this Western Mississippi [ie. Mississippian-DD] complex. Nor from this same lack of transitional steps is it probable that the styles developed there and moved South. Yet to what epoch and to what culture in Central America, on the other hand, do these forms relate?

As an inexplicable residue among the ceramics of Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador and Costa Rica, occur such traits as composite silhouette, decoration by incision [Mississippian example below-DD], support of vessels by legs or cylinders, spouted vessels, pot stands and effigy forms. These elements obtain under such conditions of antiquity as beneath the volcanic ash of Salvador, under the Old Empire Maya remains at Homul and Uaxactun, and are associated with pre-Maya material at the Finca Arevalo in Guatemala. [the traits are also present down to Peru and absent over much of Mexico, Vaillant recounts]…Doctor Lothrop and this writer designated these elements as influence Q, since we know neither their center of distribution nor their makers. This complex occupies in Central America a position analogous to the relation between the primitive cultures in the Valley of Mexico and the Toltec and Aztec cultures.

In other words, we are not only talking Mayan ceramics, we are talking old, basic traditional Mayan ceramics. Something that the country people would remember when their elite rulers had been taken away, and pottery traits which would not have been transmitted by way of Northern Mexico primarily.

As I had mentioned before, the Mississippian houses were built according to the usual Mayan plan. To be frank, these are nothing like the wigwams common in the eastern United States, they are tropical huts.

The high steep-sided roofs are designed to shed heavy tropical rainfall and designs much like this are common in Northern South America and also in Indonesia (They are also used to indicate the possibility of TransPacific diffusion between those other two regions, along with use of the BLOWGUN, which the Mayas also had. The duplication of blowgun technology on both sides of the Pacific is something that is hard for non-diffusionists to explain)

And then of course the most obvious and characteristic feature of the Mississippian cultures is the creation and use of the stepped-pyramid temple mounds, built along parallel principles but using earth instead of stone as the construction material. And this came with a version of Mesoamerican pyramid ceremonialism, placement around a plaza,human sacrifice, headhunting and veneration of human skulls.

And besides building pyramids after a design similar to the Mayan pyramids at Chichen Itza, the people carried a name by which they seem to have called themselves, Itsas. a hundred years ago or more, this was not even questioned, it was taken for granted that these people had come from that part of the Yucatan and that is why they were using that name.

POSTSCRIPT

I had begun to develop a very long and involved followup to this article on linguistics, making very involved and complicated arguments, but then I saw how the situation could be represented most easily. In the Wikipedia entry discussing the validity or non-validity of the so-called Amerind linguistic superfamily, a long list of languages is included. I excerpt part of the listing here:

Penutian–Hokan

- Penutian

- Gulf

- Atakapa

- Chitimacha

- Muskogean

- Natchez

- Tunica

- Yukian

- Mexican Penutian

- Huave

- Mayan

- Mixe–Zoque

- Totonac

IN OTHER WORDS THE MAYAN AND GULF LINGUISTIC FAMILIES ARE ALREADY CONSIDERED ADJACENT AND RELATED LINGUISTIC GROUPS.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amerind_languages

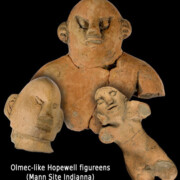

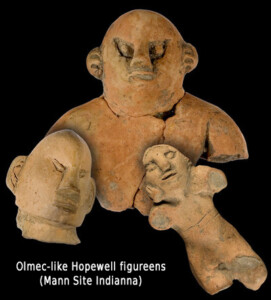

Clay figurines discovered on the Mann Hopewell Site show faces with slanted eyes, which were not a Hopewell feature. Some believe the figurines show a connection between Indiana and Central or South America.

Olmec-like Hopewell figure-ens found at Mann Site in Indianna. Other long distance trade goods, like obsidian from Yellowstone and Grizzly Bear teeth from the Rockies were found.

“It’s like Vegas … for archaeologists,” says Mike Linderman, who manages state historic sites in western Indiana. Linderman says the Mann Hopewell Site is bigger than its more famous Hopewell counterparts in Ohio, and it’s filled with even more exotic materials, like obsidian glass that has been traced to the Yellowstone Valley in Wyoming, and grizzly bear incisor teeth.

“Grizzly bears obviously are not from Indiana, never have been,” Linderman says. “There’s a theory out there now that instead of being trade items, these items [were] actually being collected by the people from Mann Site on rite-of-passage trips they [were] taking out to the West. You know, it’s something big if you’ve killed a grizzly bear and you can bring its teeth back to Indiana.”

Jaguars and panthers aren’t from Indiana, either, but they show up at the Mann Hopewell Site as beautifully detailed carvings. Put them together with clay figurines that have slanted eyes — not a Hopewell feature — and Linderman says we could be looking at a connection between Indiana and Central or South America.

https://www.npr.org/2011/01/03/132412112/the-prehistoric-treasure-in-the-fields-of-indiana?ft=1&f=1008

Exotic artifacts found at Tamtoc on Mexico’s East Coast

Perhaps the best evidence of north south trade between Mesoamerica and the Eastern United States were a serious of articacts found in Tamtoc, Mexico.

From http://www.huasteca.tomgidwitz.com/html/tamtoc.html (published in the magazine Archaeology dated to 2010)

The results may reveal links between Huasteca settlements and mound building cultures in the United States. For decades, archaeologists have theorized that North America’s Late Woodland and Mississippian cultures drew inspiration from the Huasteca, but Davila and Zaragoza’s excavations at Tamtoc in the 1990s convinced them that cultural influence, and perhaps actual migration, spread from north to south. They unearthed objects that seemed to come from the American Southeast in about A.D. 900—a fragment of a sheet of hammered copper, a pointed metal hand tool, a piece of engraved shell, a cache of a dozen whole and twenty fragmented Cahokia projectile points, and pottery that could have come from sites to the north such as Etowah, and Moundville. When they dug into a terrace beside the site’s western mound, they found that, like the mounds at Cahokia, it had been piled up layer-by-layer in basket-sized loads, with dirt from pits that became the lagoons around the site.

“We dug and dug and dug,” says Davila, “but I understood nothing.” Then he read Garcilaso de la Vega’s La Florida del Inca, an account of the 1539 Hernando de Soto expedition to the Southeast. It describes huge Indian trade and war canoes that plied the waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the rivers of the Southeast. “We think there was a migration by sea,” says Davila.

“We dug and dug and dug,” says Davila, “but I understood nothing.” Then he read Garcilaso de la Vega’s La Florida del Inca, an account of the 1539 Hernando de Soto expedition to the Southeast. It describes huge Indian trade and war canoes that plied the waters of the Gulf of Mexico and the rivers of the Southeast. “We think there was a migration by sea,” says Davila.

Scholars have long recognized that both the Southeast and Huasteca had towns with artificial lagoons and platform mounds with thatched structures on top, engraved shell jewelry, imagery of feathered dancers, stone pipes, and ghostly pots that represent the dead with closed eyes, open mouths, and filed teeth. They have theorized that the cultural influence flowed from Mesoamerica northward, but the Tamtoc artifacts, other mounds in the Huasteca, and the region’s incised shell gorgets, post-date their earliest North American counterparts.

University of South Florida archaeologist Nancy White says that major cultural influences, as well as people, may well have traveled north to south. “We know other things may have moved from North to South America, things that may be considered less important or equally important, like tobacco.” The Mississippian motifs of the Late Prehistoric period that appear in the Huasteca do indicate that “at this late time people were probably moving around and sharing these ideas, but just a few things.” In the field, Martínez and Córdova want to see for themselves.

Physical anthropologist Carlos Karam has taken bite molds of about thirty contemporary Teenek and is comparing the inherited contours of their molars and bicuspids to Tamtoc skeletons and to ancient and modern Maya. He’s checking the DNA of modern Teenek against that of ancient Tamtoc skeletons; strontium isotopes in Tamtoc teeth, absorbed in telltale amounts from drinking water, might reveal where the city’s dead grew up.

“This is a hypothesis we are testing, and we have not found enough information to confirm it, yet,” Córdova says. Martínez and Córdova think it will take ten years to complete their excavations. But just as important to them is making Tamtoc into an instructive oasis in this disrupted landscape. They plan to stock the restored lagoons with fish, reestablish the fruit trees that once thrived here, and demonstrate how ancient Tamtoc sustained itself. This year they will begin construction on a site museum and teaching center where local students will work side by side with archaeologists, study artifact restoration and conservation, and learn about indigenous people.

it is certain that people in what is now the American Southwest had extensive contacts with Mexico that would have had to included contact with Aztec, and perhaps Mayan cultures. There are trade items that have been found in both locations. We know the many of the trails and routes that the trade took place over. We don’t know if single individuals traveled the whole distance or it went form middleman to middleman, but there was contact for a long time and thus they would have known about the civilizations to the south. All the trade was carried out by people walking and carrying the goods on their backs. There was no currency, mail, stores, set prices, or banks. All trade was face to face and always would have involved negotiation. With that, as in all places that trade in this way, comes information and stories. There was no way to buy anything anonymously. Information always travels on trade routes. A person or group of people arriving form a distant culture with valuable goods would be big news every time it happened.

As Ben said, Chocolate and turquoise are some of the best evidence. But that was not all. These areas in the SW were large trading centers that connected big part of the continent in a pansouthwest trade network. It stretched to the Pacific in southern California, to the Gulf of California, north to the mobile Plains people and the sedentary plains people like the Mandan and Pawnee, east to the Gulf of Mexico, and far south to Aztec lands. Some of the items traded were: domestic turkeys, corn (maize), squash and beans, copper bells, pottery, shells of many sorts, obsidian, parrots and feathers, cotton textiles, tallow, buffalo meat, malchite, pedernal chert, lead, sillimanite, leather goods, and much more were traded.

Shells from the Pacific have been found in Mississippian mound building culture sites. Some olivella shells and abalone found at the Caddoan Mississippian site at Spiro in eastern Oklahoma originated on the Pacific coast. These would have had to have been brought by trails from the Pacific to Zuni, to Taos and then to people that brought them to Spiro. Spiro was a major western outpost of Mississippian culture, which dominated the Mississippi Valley and its tributaries for centuries. Because they were in contact with people who knew about the Aztecs it is likely they know about them too.

Here is a diagram/map of routes that pacific shells were carried by people form one culture area to the next in the SW and Southern California. All these areas were in turn connected to Aztec areas to the south and to peoples on the Plains and Mississippian peoples.

The evidence of chocolate in vessels as far north in Pueblo cultures as Utah and Colorado shows it was regularly consumed. But it was not just the cocoa beans that were traded. The way to make them into a drink was also learned and the shapes of special pottery vessels to prepare that drink was brought from the south to the American SW. Culture, technology, and information moved north. With that information would have come knowledge of large cities to the south.

Because the closest place Chocolate can be grow is south of the Aztec capital and all trade went through there, it is all but certain they knew about the Aztecs. It is possible that they traded with people on the Pacific coast but those people were in close contact with the Aztec. Turquoise that can be chemically traced from the SW is found in Maya areas.

It is I think important to remember what kind of scale the Aztec civilization was. It is also important to remember that today’s borders are random and meaningless in a historical sense. Because people were trading with the Aztecs, it is to me simply ludicrous to imagine they did not know about the Aztecs. It was definitely something people would talk about.

The main center of the Aztec empire, that controlled both the empire and managed tributary states, was a city on an island with causeways on a lake. The main market had about 20,000 people in it on regular days and 40,000 of festivals. Cortez estimated 60,000. There were 45 major public buildings. Some of the temples were 200 feet high and 262 by 328 feet at the base. The palace had 100 rooms. The most common estimate is that 212,500 people were living there on 5.2 sq mi. The Empire was multi-ethnic, multi-lingual realm stretched for more than 80,000 square miles through many parts of what is now central and southern Mexico. At least 15 million people lived in it. They lived in thirty-eight provinces.

Now think about any random human’s behavior. If you lived 1,500 miles north of Mexica and traders came every year from that huge city for hundreds of years and you sent things back there, how would it be possible not to know about it? Some people would also go south on the trails just out of normal human curiosity. There were not armed or walled borders.

Another big connection between the SW and at least as far south as the Aztecs are the ritual ball courts. They are found as far north as the Wupatki area outside of Flagstaff. It was started there in 1100CE abandoned at Wupatki in 1250 CE. It is 1,600 miles to Mexico city today. And even further on the trails that would have been used. They might have got the concept from the Hohokam, but some person or groups of people had to either seen the courts in Aztec areas or moved from those areas. It could not have come just as a word of mouth story, it is too complex and too similar. At that location, shells, salt, and cotton, copper and turquoise were traded. All those items were coming from or going to, far to the south and to the west.

The earliest Hohokam culture appears in the southwest around 300CE. About 600 CE the archaeological data shows the contact between the Hohokam and the civilizations of Mexico intensified. The southern most Hohokam style courts are in the Santa Cruz river in northern Mexico which flows north to the Tucson area. This marks the beginning of what archaeologists call the Colonial Period. Imports from the civilizations in Mexico at this time include lost wax cast copper bells, macaws (which are valued for their feathers). Pyrite mirrors from Mesoamerica, traded to the Hohokam have mesoamerican art on them. The pyrite mirrors were made from a round disk of schist on which were glued thin sheets of pyrite (a reflective metallic mineral often called fool’s gold), were traded from the Valley of Mexico. Hohokam also used other Mesoamerican food plants such as agave and amaranth as well as corn, beans and squash.

Hohokam communities built ball courts between 700 and 1100 C.E. In the Phoenix Basin, the Hohokam had some 70,000 acres under cultivation with their elaborate networks of irrigation canals. About 80,000 people lived in the Hohokam culture area. Some of the ball courts were 250 feet (76 meters) in length and 90 feet (27 meters) in width. In some instances they were dug up to 9 feet (nearly 3 meters) into the subsoil. There are at least 220 ballcourts at 181 sites across Arizona. There were probably more that were have not found and were built over.

All the rubber balls used there needed to be traded and carried on someone’s back from south in Mexico. Whether a Hohokam person did the trip or an Aztec trading caste member the people using the balls would have know they came from a far away culture to the south. It is thought that rubber balls, a cacao, and feathers, and seeds and other things came north in exchange for turquoises and obsidian and for cotton textiles. This was a regular trade, so over the centuries people in the American SW would end up with considerable knowledge of Aztec places even if they personally never went there.

Archaeologists have found rubber balls similar to those used in Mesoamerica at sites in the Southwest. The rubber had to have come from southern Mexico. It does not grow further north. The balls were made by mixing the Panama rubber tree latex with a sap from a morning glory species. This adds sulfur to vulcanize it. It is only found as far north as southern Mexico. The balls for most of the versions of the game were 3–4 inches in diameter. But there was also a version with a bigger ball hit with the hip (8 inches).

I don’t think anyone knows if items went person to person and tribal territory to territory or if some class of people did the whole length of the routes. There were many many routes and contacts over great distance however. And the current barrier of the Mexico border was not a cultural or political line. It is hard for people to think about sometimes but it only exists from 1848 onward. There was no reason to stop at that line in the past.

Pueblo people in historic times did round trips from Zuni to the Gulf of California. That is well over 600 miles to the southwest over difficult terrain. They also had routes to the Pacific, but I think those were not done by Zuni themselves but by middlemen.

There also is the well known existence of the Aztec professional long distance trader class called Pochteca (the singular is pochtecatl). To some, the people they used to carry the goods seem a lot like the images of Kokopelli that are found throughout the SW. They were high status in the Aztec world and traveled beyond the empire. They carried information and spied too. They probably are the way corn and other crops moved north into the SW. Their patron god also has a pack. These traders were certainly the ones that came north for turquoise. They don’t seem to have just used middlemen. A special subclass the Pochteca Naualoztomeca, the ‘disguised merchants’, did long distance trade seeking after rare goods. Long distance trade began long before the Aztecs from Mesoamerica in the Formative period (2500–900BCE). There was a complex system of trading centers and laws and judges that controlled the trade. The market in the north of Mexico city, called Azcapotzalco, was the one that was a trading hub and controlled all major markets and trade routes.

Long distance traders in Maya communities were called Ppolom. The Olmec had a similar caste too. The Yucatec Maya traded along the coast with large canoes with other Maya groups as well as with Caribbean communities who in turn traded to the American SE. The Ppolom were long-distance traders who usually came from noble families and leaded trading expeditions to acquire valuable raw materials. Their seagoing trade routes went from the Gulf of Honduras to Veracruz Mexico. There are also indications of contact, most likely by coastal boats, between Mesoamerican cultures and ones on the American SE Gulf coast. It is not really far by water. The boats that were described by Columbus’s brother had 25 paddlers and also passengers and piles of goods. They were 2.5 meters wide and had a small thatched shelter in the middle. It was after capturing one that they first saw cacao which was a currency in their trade. They would have mostly likely traded with the Aztecs in the Veracruz area which was a mixing place between the tow cultures. The Aztec trading class then took the cacao to the American SW as far north as Colorado and Utah in the Four Corners region.

This is the god of the Aztec trading class and below is a trader.

There is some other evidence on long distance travel. When Cabeza de Vaca finally made his way from Galveston TX through the southwest and then south to finally be able to find the Spanish a bit north of Culiacan, Mexico (Nov 1528-Jan 1536), it is certain that he was traveling on established trading routes. And when he went with the Spanish back to Mexico City from Jan to June they were traveling on established trails as well. They had not built roads and they did not go aimlessly overland.

People did go and know about things at great distances. When Euro-Americans first encountered northern Plains peoples they had high status blankets from Navajo and Pueblo weavers. They would have traded for them in Taos or Zuni. That was over 700 miles to the NE.

The Navajo stories migration of some of the clans have a pretty clear account of traveling from the Pacific near Santa Barbara all the way to near Farmington NM area. You could follow the path today. It is over 900 miles. Whether the clans really moved that way or not, it is clear that some people had traveled that distance.